It Begins to Ferment…

In 2018, I witnessed a peculiar sight one morning. My flatmate in Germany was sun-drying circular discs of leather-like material called kombucha scobies. As they glistened in the sun with a scent of warm honey, I sampled his freshly brewed kombucha. The flavour was a mix of sour, sweet, and earthy with bubbles that danced on my palate. Although it felt somewhat familiar, the unique nature of this drink, which produced a bizarre entity known as SCOBY, was intriguing.

My flatmate proudly displayed other fermented treasures: a jar of fermenting raisins for bread, and fermented vegetables like carrots and cabbage. It was the fermented carrots that jogged my memory of kanji, a North Indian beverage made from fermenting dark red or black carrots. Key ingredients like mustard seeds, black salt, and asafoetida impart a distinct flavour. In the absence of these carrots, it’s made with beets and other root vegetables, but the authentic taste of black carrot kanji remains unparalleled.

This reminiscing inspired me to introduce my German friend to Indian ferments. I quickly found a pickle recipe online and decided to make a chilli and turmeric powder, oil-free ferment, utilising the vibrant jalapeño chillies we had. I combined chopped chillies with turmeric, ground yellow mustard seeds, and salt, allowing the mixture to ferment for a week. The result was tangy, spicy, and deeply earthy.

My German expedition, primarily for academic research, inadvertently evolved into a fermentation journey. The newfound curiosity led me to experiment with various ferments upon my return, with my family as eager testers. Whether it was flavour-infused kombucha or salt-fermented fruits and vegetables, I was revisiting tastes from my childhood.

Achaars: Jars that Hold Memories of Home

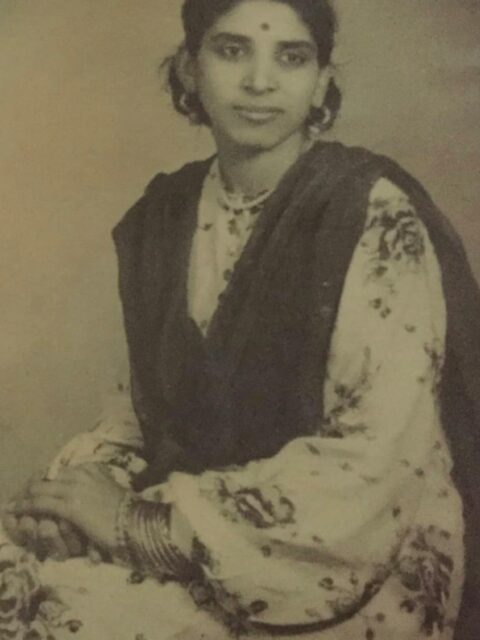

In North India, there are primarily two types of achaars. One is oil-based, often referred to as a pickle, made by blending spices, acidic agents, and mustard oil with fruits or vegetables. The other, oil-free achaar, relies on fermentation. Nimbu ka achaar (lemon pickle) is particularly revered, with some families cherishing jars passed down through generations. These lemon wedges, combined with spices and salt, age gracefully, darkening over time. I vividly recall a particularly aromatic batch made by my grandmother’s brother. She would hide it in her cupboard and knew exactly where it was. My grandmother couldn’t hide achaars from me.

Achaar preparation is a cherished ritual in North Indian homes, with some individuals being lauded as experts. Unlike routine cooking, achaar-making hinges on environmental factors, making it a delicate and sometimes unpredictable art, surrounded by customs and superstitions.

Despite its traditional nuances, I believe that with passion and curiosity, anyone can master the craft. However, what distinguishes an achaar maestro is their intuitive flair. It’s more than just a technique; it’s an art that reconnects you with your intuition.

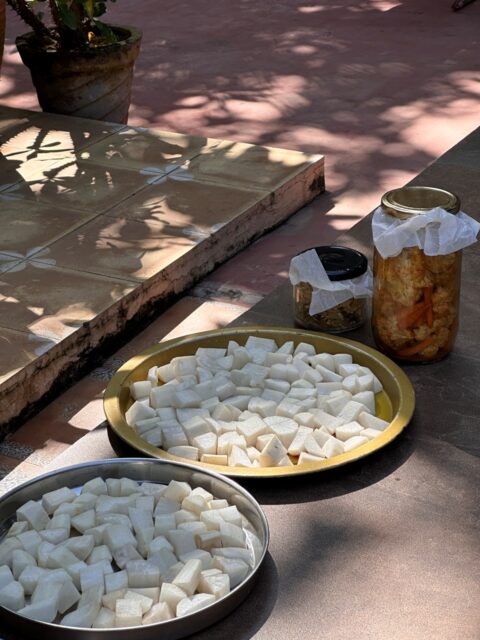

I recently prepared nimbu ka achaar with my mother. We sun-dried lemon wedges and coated them in a spice blend of salt, peppercorns, black cardamom, long pepper (pipli), and black salt. After a month, during the Delhi winter, our achaar was ready to savour.

Kanji: Roots We Ferment

Delving into the world of fermentation helped me unravel its mysteries. Kanji, a fermented black carrot drink, became a symbol of my understanding. Just like other home ferments, Kanji would make its appearance during winter, vanishing after a brief spell. Its preparation, seemingly conjured by my grandmother, mother or aunt, tasted so distinctive that it seemed like magic.

When I became curious about Kanji, my grandmother wasn’t there for guidance. So, I turned to her sister, seeking memories of pickling, preserving, and making Kanji. One profound insight she offered was on the role of salt: she intuited its quantity, knowing salt would halt the ferment. I visualised everything coming to a standstill upon salt’s addition, allowing a new world to emerge in the jar. Salt, in essence, establishes a sanctuary for certain microorganisms. Crafting my own Kanji as an adult became an empowering endeavour.

To prepare black carrot Kanji, one places large carrot chunks into a sizable jar, adding coarsely ground brown mustard seeds, red chilli powder, asafoetida, salt, kala namak (black salt), and water.

Thereafter, my journeys have been enriched by a newfound appreciation for preserved and especially fermented foods—a fascination rooted in my childhood.

Gulkhand (sugar-fermented rose petals with a jam-like texture), jamun vinegar, mango wine, fermented rice left overnight, axone (fermented soybean), fermented bamboo shoot, fermented radish achaar, sugarcane vinegar, kanji, khar (a preserve typically from banana peels), and ngari (fermented fish) represent a plethora of flavours: earthy, tart, sweet, astringent, salty, pungent, and bitter. Touring homes across India reveals countless such delights. Most people would proudly share their recipes, often emphasising their benefits for gut health.

Fermenting Red Chillies: A Burst of Heat and Flavours

While many ferments cool the stomach, chillies have the opposite effect, offering a fiery kick that can sometimes be discomforting. It’s the capsaicin in chillies that elicits this sensation. Yet, chillies, when consumed judiciously, offer a delightful taste experience.

Fermentation intriguingly moderates their heat while amplifying and diversifying their flavours. Thus, chillies can both complement other ingredients or be the star themselves.

Dalle chillies, native to Nepal, Sikkim, Darjeeling, and Kalimpong, are particularly cherished. These chillies, like many perishable produce, are preserved post-harvest. On a visit to Namchi, Sikkim in November 2019, I was introduced to the vibrant Dalle Khursani. These fiery red orbs were omnipresent—drying on bamboo baskets, pickling in jars, or gracing kitchen countertops. Often, Dalle chillies are combined with radish or kinema (fermented soybean), and sometimes even with yak buttermilk. Witnessing these chillies sun-drying on rooftops was an unforgettable tableau, their enticing aroma permeating the air.

During a 2022 trip to Damak, Nepal, I encountered these chillies once again. Eager to preserve their essence, I fermented them, ensuring they’d remain fresh upon my return to India. The resultant chillies, aromatic and juicy, were a testament to fermentation’s magic.

India’s diverse regions, from Andhra Pradesh and Kashmir to Rajasthan and Nagaland, boast unique chilli varieties, each with its distinctive flavour and heat profile.

Mango Orchard: A Fermentation Playground

It’s mango season, and the farm, located in the Chittoor district of Andhra Pradesh, is bustling with activity. Mangoes, with their intoxicating fragrance, are being gathered in tons. Among these are mangoes fallen to the ground, bitten off by hungry monkeys. These ground mangoes undergo natural fermentation due to the action of yeasts on their sugars, producing ethanol, commonly known as alcohol. Monkeys return to feast on these fermented delights, much to the humans’ dismay.

During my last two visits in mango season, I tapped into the power of fermentation. Each mango variety offers unique fermenting potential: some suitable for hot sauces, others for vinegars, and yet others for pickles. We chose the sweetest mangoes for brewing vinegar, capitalising on their high sugar content for the yeasts to feed on. In contrast, acidic, pulpy mangoes ideal for pickles transformed our courtyard into a pickle-making unit. The result? Punjabi-style mango pickle with spices like fennel, onion seeds, and fenugreek, pickled in mustard oil. And an Andhra-style version, sun-dried extensively, alongside a fermented mango pickle, one batch pure and the other mixed with local sesame oil.

Hot sauce was another exciting experiment. Andhra Pradesh’s renowned red chillies combined with sweet totapuri mangoes to create a tantalising sauce. The recipe: chunky pieces of mangoes and chillies, salted and fermented for a week, blended into a paste and fermented for another week. This sauce had the right balance of spice, tartness, and sweetness.

Local produce and fermentation knowledge truly open up endless possibilities!

Fermented Fish: A Tale of Preserved Recipes

Fermentation has a rich history in India, used for medicinal properties, preservation during scarce times, or simply for the love of flavour. Among the many preserved foods, fish holds a special place. Particularly in regions around the eastern Himalayas and north-east India, fish fermentation – intriguingly without salt – has been a longstanding tradition.

Ngari, a preparation from Manipur, exemplifies this tradition. Made from punti fish, these are sun-dried and fermented in tall earthen pots, producing a pungent, earthy flavoured delicacy over months. I was first introduced to ngari during my hostel days. My roommate, a native of the region, taught me to make eromba, a chutney blending boiled vegetables with ngari. Even now, eromba remains a cherished dish for me, bringing back fond memories of shared meals.

Celebrating the Beginning of New Creations

Exploring fermentation in India is a journey of discovery. The similarities in fermentation techniques across cultures are astonishing. This article offers just a glimpse into the vast world of fermentation. One recognises the deep reverence for fermented foods in communities everywhere. Every step, from selecting the fermentation vessel to the final rituals, is carried out with love and care. These rituals, during and after the preparation time take different forms- songs, worshipping of Gods and Goddesses, a warm pat on the jar, simply a pause, silence or conversations about everydayness – all this to celebrate the beginning of a new chapter for the ingredients and send out good wishes for happy ferments.

Anshita is a fermenter. She makes ferments, holds fermentation workshops and gets to learn about the world and herself through the art of fermentation. She enjoys cooking with ferments as well and takes care of different kinds of jars with ferments in her kitchen. She transitioned to practising fermentation after pursuing academic work in German literature for many years.

Eager and curious about getting to know fermentation and preservation ways and methods in places she travels to, she is inspired by her own and other cultures and also derives inspiration from friends and other fermenters.

She also believes that fermentation plays an important role in bringing sustainability to our homes and farms and that there is a lot that we can learn from our ancestors. Through innovation, experimentation and learning, fermentation opens up a world that is good for both us and the ecosystem of which we are a part. She aspires to take this message to places.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.