Foreword

When we first heard Dr. Tarana speak about her research work connecting the historical dots of Rampur, her persistence to reinforce the culinary contours of the nineteenth century epicenter of North Indian Muslim culture, struck a chord with us.

Reviving aspects of Rampur cuisine through groundwork, interviews and recipe experiments; and reinstating Rampur on the culinary map of India became a personal journey for her.

This journey comes to life in her book, Degh to Dastarkhwan: Qissas and Recipes from Rampur, which follows the historical arc of Rampur cuisine as it mirrors the political and economic events of the past two centuries. Within the context of food, and through the social bonding of dishes like khichdi, she invites her readers to view Rampur and Rampuriyat from a socio-cultural lens. She also foregrounds the unmentioned women – the practitioners and custodians of culinary history and culture. Her book resonates with the voices of these women, their perspective on food and the great generosity with which they shared their family recipes.

This article is a brief window into the book, which celebrates Rampur cuisine with anecdotes and resurrected recipes, and which painstakingly attempts to anatomize what really constitutes and distinguishes it. Dr. Tarana took us on such an immersive experience through Degh to Dastarkhwan, that we found ourselves trying out a recipe or two, and somehow, the book unintentionally but tangibly entered our kitchens.

“Arey Bibi how could I eat till I had sung for the Nawab? Then by the time the performance was over, it was morning, and we were too tired to eat. There were so many dishes––thirty types of pulaos and biryanis, qorma, kundan qaliya and kababs you could eat with your lips.” Mahpara Begum, a court singer trained by Nawab Raza Ali Khan (ruled 1930-1949) would often regale us with fascinating food and music stories from the erstwhile Nawab of Rampur’s court. Sometimes her voice would dip down to a gossipy low but that was after we had bribed her with a cigarette or two. I was told by my husband to take her stories with a pinch of salt but the thirty pulaos intrigued me. We had only one style of yakhni pulao in Rampur now.

I grew up with the unchallenged family belief that there was no food like Rampuri food. Food was never central to my life, and I deplored the preoccupation with the correct balance of masalas, the perfect consistency of curries and the fluffiness of rice. For me all qormas tasted the same, and I blasphemously used the terms ‘pulao’ and ‘biryani’ interchangeably. Maybe I was taste challenged, or in denial. My culinary enlightenment began by a strange coincidence; when I look back now, I’m tempted to believe that it was a quizzical alignment of stars by God on a good humoured day.

On my return to Rampur in 2010 I had started studying the cultural history of my ancestral town at the magnificent Rampur Raza Library whenever I got the opportunity. I would sometimes write articles for newspapers on dastangoi tradition, poets and other cultural aspects of Rampur.

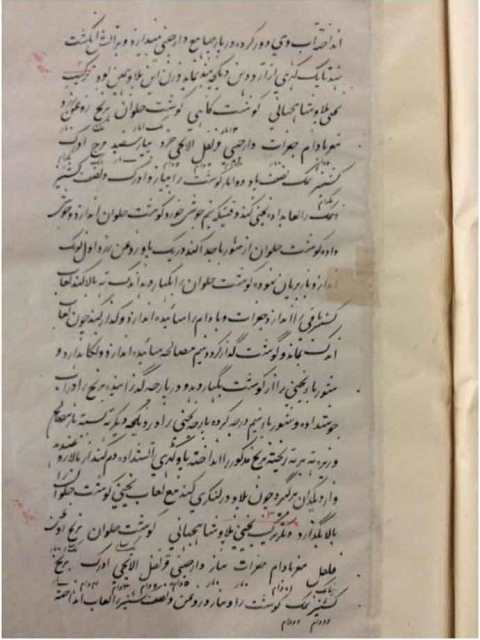

A cataloguer pointed me towards Persian cookbook manuscripts preserved at the library. I knew no Persian and could just about read Urdu but presented myself to the librarian demanding to see the manuscripts. The librarian asked me if I knew the Persian word for the art of cooking. I didn’t, and so was summarily dismissed. Rampur has great respect for genealogies and my ancestors were the first settlers of the town in 1774. A visibly miffed librarian was ordered to assist me in my research and the manuscripts were handed to me.

I could only read the names of more than two hundred dishes detailed there because Urdu and Persian have the same script. Most of the dishes were unheard of even by the old timers I reached out to. Were all these cooked in Rampur? As I started translating a cookbook volume with the help of a more tolerant member of the library faculty and gathering oral history around food, I was filled with great anxiety. We had disremembered so much and were still in the process of losing the contours of this meticulously developed cuisine. Rampur cuisine was already indistinguishable from other north Indian cuisines. Till a generation back Rampuri cuisine had a repertoire of dishes which could rival the fabled dastarkhwans of Mughal emperors. Vivid descriptions of the banquets hosted by Nawabs of Rampur are found in written histories of the time.

Most of these dishes have become intergenerational food memories- talked about but never experienced. Thus, foods like dar e bahisht, kundan qaliya, hubabi, the vast repertoire of biryanis, qormas and kababs, among others, became the subject of mythical food nostalgia.

Rampur, a Rohilla Pathan princely state established under the British, became the cultural node or markaz of north Indian Muslim culture in the nineteenth century. Stationed strategically between the fallen giants of Muslim culture – Delhi and Awadh – it was prosperous enough to absorb the destitute artists fleeing the destruction of 1857. The Nawabs of Rampur became the patrons of all forms of art and culture. Around the beginning of nineteenth century, a conscious effort was made by successive Nawabs of Rampur to textualize the Rampur cuisine and to create and innovate dishes that excited the Pathan palate with basic but intense flavours. Thus, the chefs and sou chefs from Rampur, Delhi and Awadh collaborated to create and present a new ‘haute cuisine’.

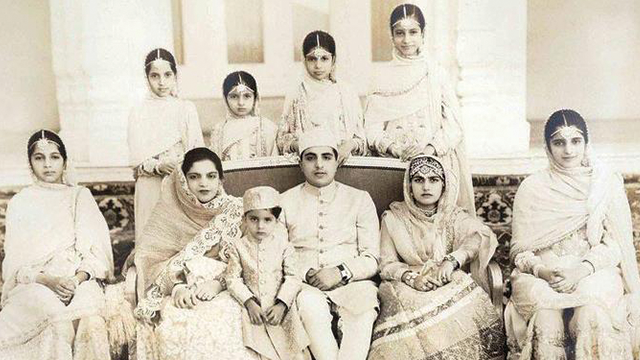

The cookbook manuscripts which I accessed at the Rampur Raza Library were collected, commissioned and written in nineteenth century, a time of cultural amalgamation and gentrification. Later, Rampur cuisine would become an essential element of ‘gastro-diplomacy’ as Nawab Hamid Ali Khan (ruled 1889-1930) and Nawab Raza Ali Khan (ruled 1930-1949) would entertain at their lavish tables serving a menu of 200 dishes.

Unfortunately, the post-independence decline of this cultural node following the abolition of royal privy purse is reflected in the forgotten aspects of the cuisine and its culinary practices. Princess Naghat Abedi, Daughter of Nawab Murataza Ali Khan (1923-1982) reminisces about the dishes she ate at her father’s dining table till the late 1970s barely a generation ago. She managed to write down some recipes before the master khansamas of the cuisine hung up their ladles.

What is Rampur cuisine and how is it different from other north Indian Muslim cuisines? This formed the core of my search. I started reimagining and giving practical shape to the translated recipes.

My old khansama was surprised and amused at my sudden interest in cooking and tried to make sense of the instructions I read out. The procedures and the vocabulary of cooking had totally undergone a change. The recipes were cryptic in their instructions. ‘Add proper masalas’ I was commanded; ‘keep watching’ was an oft repeated order presupposing that we had nothing better to do. The measures were in dam, tola, masha and chatank and I valiantly tried to convert them to modern equivalents. Numerically challenged as I am, I once measured out 550 gm of cinnamon for a pulao!

Muddling through culinary disasters, consulting khansamas and older women in the family, I started writing about Rampuri cuisine. One of my articles caught the attention of Professor Siobhan Lambert Hurley from the Department of History at Sheffield University. As we connected ––and God continued ordering my cosmos with his ironic humour–– the AHRC funded Forgotten Foods project was born, and I became a project consultant and subsequently a research fellow at the University of Sheffield. I even reactivated my dormant taste buds though I heavily depended on my husband and mother for the final verdict on the now(thankfully) project sponsored culinary experiments.

What I discovered through my translations and its practical application as well as delineating the cultural context in oral history was that, briefly put, Rampur cuisine had a certain melding of spices which was not overpowering but delicate; though inspired by Mughal and Awadhi cuisines–– and leaning heavily on the latter–– what developed in Rampur was a distinct style and taste which had the rustic element of its Pathan culinary roots. It was also defined by the hardy temperament of the Rohilla Pathans which favoured more forthright flavours. We Rampuris learned the art of presentation from the Awadhi khansamas who found sponsorship at the royal kitchens, where more than a hundred khansamas worked to amalgamate and innovate dishes to win the favour of the Nawab.

As the number of khansamas of the royal kitchens were downsized in the parsimony of post-independence era, the khansamas carried away the skills and gains of a carefully curated cuisine hastening the decline. For me reviving aspects of Rampur cuisine and putting Rampur back on the culinary map of India became a personal journey.

The social impact aspect of the Forgotten Foods project allowed me to work with the local khansamas and support them through the economic deprivation of covid lockdowns. I essentially tried to give them back the repertoire their earlier generations had practiced but had not passed down. This economically fragile segment became the ambassador of the revived and resurrected cuisine of Rampur.

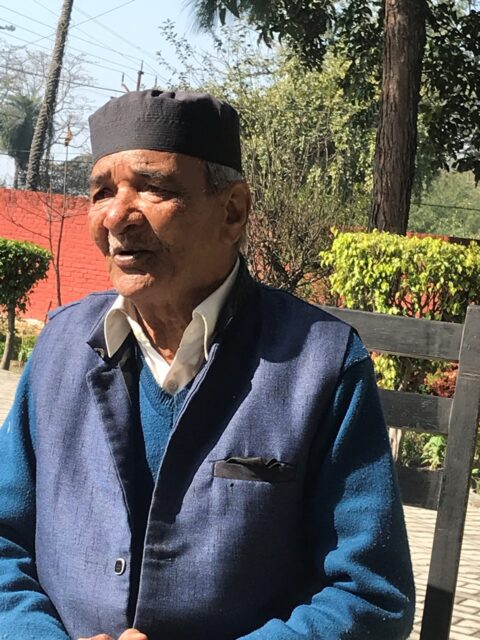

Unsurprisingly, they were quick to connect the translated recipes with the food stories they had grown up with. A few Rampur khansamas cater to clients outside Rampur and go for stints at hotels, the enhanced menu meant increased employability. Majid Khansama is the last living khansama who worked at the Khasbagh palace for Nawab Murtaza Ali Khan (1923-1982) and later his daughter Shehzadi Naghat Abedi. Majid bhai narrates details of the Khasbagh kitchens located behind the main palace; there was a separate rice kitchen, sweet kitchen and English kitchen.

The kitchen block and stores are inaccessible today. The food was cooked on coal fired bhattis and about thirty cooks were employed at that time–– a huge downsizing from over a hundred cooks employed by Nawab Hamid Ali Khan. Majid was trained in the English cuisine––rather a style of Anglo-Indian cuisine developed in Rampur––by his father Ashiq Khansama who had been sent abroad by Nawab Raza Ali Khan to learn the culinary art. A staunch loyalist, he fondly remembers how as a young apprentice he saved the day and cooked up a full lunch in record time when unexpected politically important guests arrived one morning.

The other khansamas hadn’t arrived yet. He was the last few of the khansamas who remained with the family through thick and thin. He was summoned to the dying Begum Rampur’s bedside in Bombay and the hospital was instructed to let him visit her–– a mark of affection and closeness that the begum felt for him.

Creating awareness and exciting interest around Rampur cuisine to drive up the demand was the next aspect of our focus. We recorded food stories and oral histories in the form of a documentary. The eight hour long footage features interviews with members of the royal family sharing their food memories and their tables, talks with the local khansamas coming from a long tradition of royal khansamas as they cooked the traditional dishes for us.

We participated in and filmed a food tasting event – Zaiqa e Rampur – organised by the district administration of Rampur, which had an amazing variety of sweetmeats and halwas from turmeric halwa, ginger halwa, neem halwa and hari mirch halwa to garlic kheer.

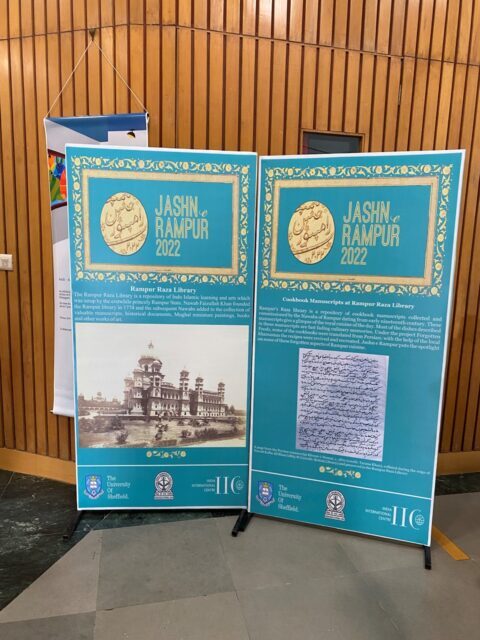

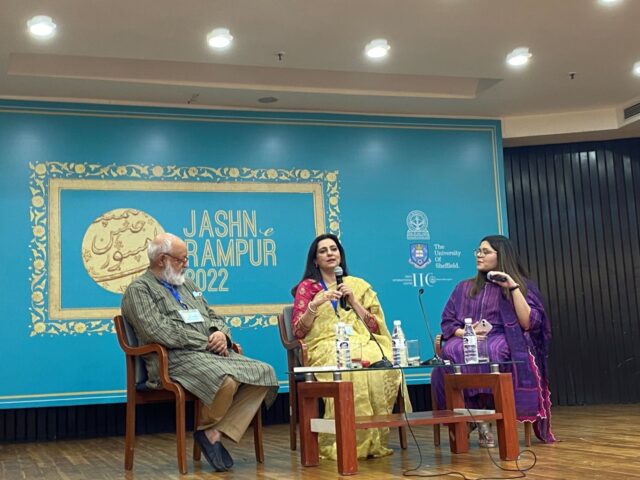

This documentary was released at our recent food festival, Jashn e Rampur, and will be archived at the University of Sheffield. Partnering with the local government, I published a booklet on Rampur cuisine which had the contacts and repertoire of all the Rampur khansamas, home catering establishments as well as street food vendors––a yellow pages of sorts for restaurateurs, hotels or ordinary gourmands.

Food writing and publishing anthologies is a great way to connect cuisines and garner interest. Desi Delicacies, an anthology of food writings on South Asian Muslim cuisines published by Pan Macmillan in India, under the aegis of the project, became a bestselling title on Amazon. It was published as Dastarkhwan by Beacon Books in UK. A second volume of anthology on South Asian Muslim culinary cultures is on the anvil.

The one-day Jashn e Rampur hosted in collaboration with and at India International Center, Delhi on the 28th of October 2022 focussing on the culinary heritage of Rampur in interaction with other locations in north India, marked the culmination of the project. In the late nineteenth century, the Rampur court was known for its patronage of an important cultural festival, the Jashn e Benazir, featuring poetry, music, and food at the Nawab of Rampur’s Benazir Palace.

Bringing this historic model to life in a contemporary context, the Jashn e Rampur spotlighted several aspects of Rampuri culinary culture – rediscovered, researched, and resurrected through the Forgotten Foods project. The event was a great success with a footfall of about 500 attendees throughout the day. The sessions on oral food history, book launch of Degh to Dastarkhwan, the Dastarkhwan e Rampur documentary and rekhtigoi performance by inimitable Fauzia Dastango engaged a rapt audience.

We also had a blind taste test featuring khichdi prepared from a near extinct heritage rice variety, the Tilak Chandan grown at Benazir Farms in Rampur.

The dinner by invitation in the rose garden of IIC featured 17 Rampuri dishes translated from historic texts and reimagined by the Rampur Khansamas lead by Aslam Khansama and his team.

Some of the dishes were Do-gosht Pulao, Seekh Kabab Nargisi, Kundan Qaliya, Pineapple Pulao, Shabdegh, Adrak Halwa and Gulathhi.

Looking at the intrigued faces of the guests as they tried out the reimagined heritage dishes of Rampur cuisine and answering their queries, I recalled a poignant line in one of the Persian cookbook manuscripts:

Dar kami o beshi ba ikhtiyar e hast

The abundance and paucity of everything is in our hands.

The khansamas of Rampur measuring out flavours with the practiced flick of their wrists, who had learned the culinary skills as soon as their hands could turn the ladle in the deghs, know this secret wisdom of flavours and life. Maybe this unexpected journey brought me to this brilliant insight.

Dr Tarana Husain Khan is a writer and cultural historian. Her writings on the oral history, culture and the famed cuisine of the erstwhile princely state of Rampur have appeared in prominent publications such as Al Jazeera, Eaten Magazine, Scroll.in and in the anthologies Desi Delicacies (Pan Macmillan, India) and Dastarkhwan: Food Writing from South Asia and Diaspora ( Beacon Books, UK). She is the author of historical fiction, ‘The Begum and the Dastan’ which won the Kalinga Literary Award for fiction, was shortlisted for Women Writer’s Award by She The People, and Longlisted for Auther Award.Her book on Rampur cuisine, Degh to Dastarkhwan: Qissas and Recipes from Rampur has been published by Penguin Random house India.

She is currently working on a Research Fellowship at the University of Sheffield for an Arts and Humanities Research Council funded project, ‘Forgotten Food: Culinary Memory, Local Heritage and Lost Agricultural Varieties in India’.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.

1 comment

very nice tips