I first saw Fouzia perform ‘dastangoi’ (an Urdu artform of immersive storytelling) many moons ago in Delhi. In a lot of her work, she often draws upon sensory memories from her childhood spent in Old Delhi. Since then, I’ve wanted to hear her stories and the stories that inspire her stories. We met for coffee and more than two hours went by without any sense of time.

From her most exceptional of experiences, Fouzia repeatedly recalled with a transfixed expression, this machli ka salan, made by one Saira Begum, a close family friend, whom all her friends and family fondly call Shama Apa or Ammi.

She bullishly declares, “kabhi purani dilli ke gharon ka khana khao, baaki sab bhool jaogi,” (eat home cooked food in Old Delhi once, you’ll forget everything else). I’ve heard such tall claims ten a penny, but Fouzia’s words had nothing figurative or hyperbolic about them. She meant every word of it when she suggested I make a trip to Old Delhi for Shama Apa’s Machli Ka Salan. I had to witness the Purani Dilli that galvanizes her stories, so I went.

***

Saira Begum has been living in Ballimaran for the past 50 years. The gully leading to her house has been shovelled – a routine state of affairs here – and is unapproachable, so we meet at her daughter’s nearby.

As a tourist or a shopper, when you’re walking through these lanes, you don’t tend to look above eye level or take a staircase unless a shop is located on an upper floor. But, somewhere between the second floor and the terrace of these towering gridlocked buildings, exists a whole other microcosm of the Old Delhi culture.

We followed Fouzia’s instructions and disappeared into one of the many walls of the walled city. After climbing four, maybe five flights of very steep stairs we forgot the count. The staircase landings and corridors were utilized to the hilt, with shoe racks, washing machines and clotheslines taking up any spare space. We reached the top floor, gasping and gulping, with whetted appetites and dizzying heads.

The door of the house led us into a veranda. Several doors fringing the veranda opened into separate rooms of the house. We entered a room with a bed in one corner, its floor lined with dhurries, where Saira Begum, her daughter Azra, her son-in-law Fahim and Fouzia – the raconteur of our story – all of us sat down for a round of introductions and recollections.

For the first 30 minutes Saira Begum barely spoke. She found our purpose of documenting her cooking quite absurd. One thing was incontestable from the outset, there was no scope for direction or scripting as far as Ammi’s cooking was concerned. She was going to do her thing and we would attempt to record it. What she couldn’t fathom was why exactly we were here to see her. Some people who loved her thought that she cooks too well to go unnoticed; but far too many people said that about their aunts and mothers and grandmothers. Sure, we would know better than to fall for this trope? Why were we interested in watching her cook in this chaotic kitchen?

When asked if she remembers her days of cooking on an angeethi, she was quick to let the gathering know that she has mostly cooked on the stove. “Haan, angeethi thi magar hamare time par toh hamne gas pe hi zyada pakai hai.” (translation: yes, we had an angeethi, but in my time, I’ve mostly cooked on the stove.) She succinctly deglamourized our idea of women cooking on an angeethi for hours.

When asked how she cooks a dish purely by instinct, how is it that no one can cook this salan like her? “Chammach se naapke daalte hain, fir kam zyada ho toh usko theek kar sakte hain,” (translation: everything is measured with spoons, then adjustments can be made according to taste), Shama Apa confuted.

It must be true that Saira Begum and Shama Apa and Ammi makes the best machli ka salan, because whoever knew either one of them, said so. Everyone around her kept gushing about her salan and maghaz and biryani making skills. No one mentioned much else about her. After all, she was wedded at the age of 16 and by that time she was already a skilled cook.

She reigns, as it were, in the kitchen and in matters pertinent to cooking, she listens to no one. That’s where you could see her for who she really is. She is the matriarch as far as anything related to food is concerned and she ascertains that with a dogmatic tendency at times.

Like when Fahim Saab described ‘shola’, a classic Old Delhi meal: “aaj korma bana, humne khaya, thoda bacha humne usko freeze kar diya, kal keeme mei koi cheez bani, wo bach gayi usko freeze kar di, aise 4-5 cheezein mix karke khichdi banai jaati hai, that is called shola.” (translation: say we made korma today and there’s some leftover, we freeze that; tomorrow if we make some type of keema and there’s some leftover, we freeze that as well; we combine 4-5 such dishes and make a khichdi, that is called shola.)

Fouzia chimed in: “usme paalak dalta hai aur bhagaar lagta hai phir, aur mujhe ye haleem se zyada acha lagta hai, waisa hi flavour aata hai isme.” (translation: spinach is added to it, then it is tempered and I like this more than Haleem, the flavour is somewhat similar.)

Shama Apa, who was patiently heeding the others, shared some crucial details: “chawal daal dalta hai, usi mei salan dalta hai aur paalak dalta hai, fir uski ache se ghutai hoti hai aur wo bada maze ka shola banta hai phir.” (translation: rice is added to it, then salan and spinach are also added, then it is continuously stirred and cooked, then the shola comes out well.)

Whenever someone shared a note about a dish or its process she would have the last word with an authority that no one could disregard.

Inside the kitchen, Shama Apa had already begun her work and we quickly jogged after. She wasn’t cooking for the camera, she didn’t care for it, she never looked at it. She only seemed worried about the hype that had been created around the dish. She kept wishing for it to turn out well and those around her kept reassuring her that it would.

Fahim Saab gave us a quick briefing that the singhada (catfish) or malli fish (helicopter catfish) is used to prepare machli ka salan since both of these have very less bones.

As he began to explain the cooking process, Shama Apa took over, “Machli se bisand ko hatane ke liye isme namak lagaya jaata hai, ek ghanta namak lagane ke baad usko dho diya. Jab uska pani khushak hogaya, tab usme 2-3 nimbu ka ras lagate hain, aur usko ek ghanta rakhte hain, isse machli toot ti nahi hai. Hamare bade bhi isi tarah bnate the.” (translation: to remove the foul smell, we first rub salt on the fish and leave it for an hour. Once it releases its moisture, we marinate it with the juice of 2-3 lemons and keep it for another hour, the lemon will make the fish firm and prevent the pieces from breaking. Our elders also made it this way.)

The degh was set on the stove and almost half a litre of oil was heating in it for 3 kilograms of fish being prepared for the day’s visitors. About 5 heaped spoons of a fine paste of cumin, black pepper, black cardamom seeds, garlic and ginger, – that Ammi uses for salan – went in first.

Then, red chilli powder – 3 heaped spoons

Dry coriander powder – 9 heaped spoons

Green cardamom – 10-12 whole pods

Clove – 8-9 buds

Salt to taste

Shama Apa patiently explained: “iss masale ko tel mei 2-3 baar bhun na padhta hai taaki saara paani khushak ho jaye, kyunki dahi aur machli mei se bhi paani niklega.” (translation: this masala needs to be cooked in oil 2-3 times so all the water evaporates, since the yogurt and fish will also release water.)

She then added a small spoonful of turmeric to the half-cooked masala. After cooking the masala for over 30 minutes, about 1 kilogram of yogurt was added to it.

“Waise 250 gram bahut hai ek kilo machli ke liye, agar dahi khatti ho toh kam dalti hai, agar khatti nah ho toh thodi zyada dal sakti hai,” (translation: Typically, 250 grams of curd is enough for 1 kilo of fish. If the curd is sour, less curd is used, if it isn’t, more can be added.) Ammi kept dropping these little footnotes of wisdom, here and there, while she cooked, expecting us to grasp and recreate this dish later.

It was time for her evening namaaz, so she handed the degh over to Fouzia and asked her to keep stirring it till she returns. Watching Shama Apa cook was an intensely emotive memory for Fouzia, and she stood there by her side, shadowing her in the kitchen all evening. And while Shama Apa did not seem to believe in the idea of a sous chef, she generously welcomed us all into her kitchen, tolerantly answering all our pesky questions.

Ammi returned promptly, wary of leaving her salan unsupervised for too long. Once the masala was almost done, she added half a cup of water and cooked the masala again. The whole process took about an hour.

“Isko hilate raho taaki masala jale nahi. Jab masala mei dana aa jaye tab ye ho jaega,” (translation: keep stirring the masala so it doesn’t burn. The masala will be done when it becomes thick and granular.)

The tedious process of placing the fish in the degh began next. Shama Apa segregated the pieces from the tender to the more tough ones and put the heads and bigger pieces in first.

She explained that the head goes in first since it has bone, weighs more and takes most time to cook. The fins and gills go in last and are taken out first to prevent them from becoming mushy.

She didn’t just dunk the fish in, each piece was strategically placed according to the amount of heat, space and masala required. This took a while.

Without touching the ladle to the fish, she carefully coated the masala onto the pieces. “Shuru mei toh chammach chala sakte hain lekin baad mei degh ko hi utar utar ke hilana padhta hai, chammach nahi lag sakta fir, nahi toh machli toot jaati hai,” (translation: We can use a ladle in the beginning to stir the fish, but once it cooks, the vessel has to be taken off the stove and swirled around, otherwise the fish will disintegrate.) she instructed.

As the number of pieces increased she stopped using the ladle. She removed the degh from the stovetop, kept it on the floor and swirled it around. “Hamara taambe ka degh iss tarah ka hota hai, neeche se gol, jis se isko ghumaya ja sake.” (translation: this cupronickel vessel has a rounded bottom which is well-suited for rotation.)

She repeated this process several times, pausing and keeping it on and off the stove.

Once the fish and curd started releasing more water, she evenly scattered 4-5 spoons of fried, pound onions. These onions are fried in ghee, then frozen. Once they harden in the freezer, Shama Apa hand pounds them and stores this powdery mix in a box in the freezer. Even though some shops in Old Delhi have started selling these onions since the last 4-5 years, she recommends making this at home. The bazaar ones are machine fried and she prefers frying them in ghee, since this is used in many other traditional dishes like korma.

When the masala started to stick to the bottom, she said, “ye acha hai, ab thoda aur paani dalega,” (translation: this is good, now a little bit water can be added.)

She added some water and kept rotating the degh. She recommends staying away from the ‘dum’ method when preparing this dish, to prevent the fish from turning mushy.

While she sincerely believed that she follows a standard operating procedure, she made small tweaks at every step, adjusting the masalas, the heat, the moisture… making it impossible for anyone to really recreate this masterpiece.

The evening coffee arrived and Azra suggested that she could lower the flame for a while and drink her coffee first. “Na na, aanch halki nahi karungi, sahi lapat honi chahiye” (translation: no, no, I won’t reduce it now, the flame should be right) Ammi refused, as though it would be the biggest mistake to make at this point. She quickly sipped the coffee with one hand while moving the degh around with the other.

The kitchen, rooms and veranda were sensationally redolent of Shama Apa’s Machli ka Salan. All the spices and ingredients had synthesized into one utterly gratifying meal. It is impossible to really describe the taste of this salan.

Fouzia, who has known this dish very closely, described it aptly, “Ammi ke salan mei tari machli ke andar baithi hui hoti hai.” (translation: In Ammi’s salan, the curry is sitting inside the fish.)

When the salan was done, Ammi stepped away, a pensive smile beginning to appear on her face, ”hum apni ammi ko aise hi khana pakate hue dekhte the.” (translation: I used to watch my mother cook just like this.)

“Sab bolte hain aap baith jaao, hum khilaate hain, mai baith gayi toh ye chammach daal denge aur phir wo cheez kharab ho jaegi, mai kisi ko haath nahi lagane deti,” she asserted. (translation: everyone keeps asking me to sit down, and say that they’ll serve. If I sit down, they’ll put spoons in the dish and spoil it. I don’t let anyone touch it.)

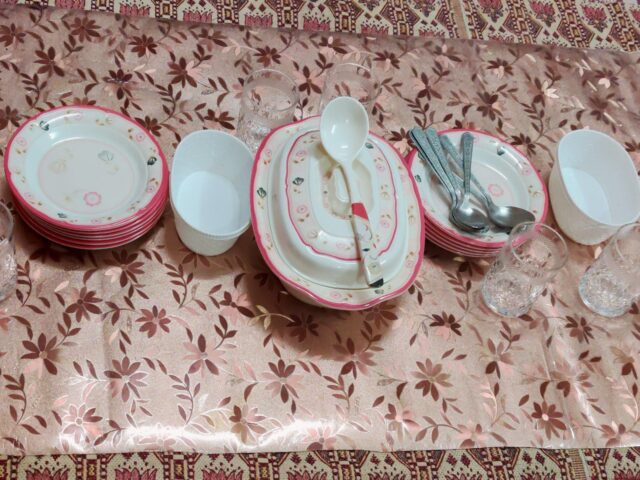

The dastarkhan (a ceremonial dining spread) was laid out and as we all sat down to eat, we asked Shama Apa about the food her mother used to make, and she said, “kya bataein, hamari ammi sabse acha khana banati thi… laal roti, aaloo gosht aur korma degh mei banati thi, kisi bhi hotel se behtar.” (translation: What do I tell you, my mother used to cook the best food… she would make leavened bread, potato and mutton curry, and korma, better than any restaurant.)

There was no food in this world that could challenge her mother’s. Then the trope must be true.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.

1 comment

Loved the way her recipe was presented to us with all those emotions she conveyed intact👌🏼✨