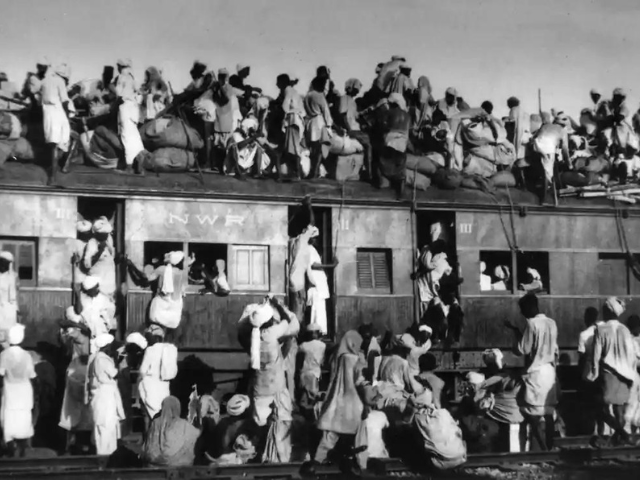

Partition of Indian mainland to India and Pakistan is an event that has impacted in one and many ways but mostly in the sense of losing something. It was a one of its kind event where people migrated and were massacred in such large numbers. They lost their lives, possessions, dignity and most profoundly, their stability and legacy.

At the time, when culture and traditions were dying a slow death, many of their foodways and their culinary culture also either died or reached the other side after being highly appropriated. It is natural for any human being to practice his/her ethnicity to the maximum extent possible. But environmental factors and availability of ingredients often leads to abridged or appropriated versions of recipes. Even then, the recipes of partition are still not highly abridged due to the simplicity of their nature, as they were developed with whatever was available.

These recipes were driven by two factors – optimization of resources and the timing of fire from the chulha. Most of them didn’t even have proper names and were named after the major ingredients of the dish like doodh di sabzi, malai tadka, awale di sabzi, adrakh ki chitt, mitthe chawal. And not to forget dudh-patti – this quintessential drink runs across Pakistan and parts of northern India, the finesse of which is measured by its color, how surkh (reddish-brown) the concoction is, depending on how long it is boiled for, to attain the required color.

For instance, making baigan da bharta by charring the eggplant in the fire of the chulha; making of kadhi because buttermilk was available as churning butter was an everyday activity. (The truth about the excess of milk and milk products in Punjab on both sides of the border needs no introduction).

So here I’ve made an attempt to revive two of the milk-based recipes – chhitt and awale di sabzi. These recipes are not dying as they were already living a mundane life. They were not dishes made on certain festivals, they existed for survival. However, each recipe, no matter how simple it is, needs to be celebrated, recorded and shared. These are recipes of survival and intuition and about how the entire day was consumed in cooking three meals for the family. My grandmother tells me how for breakfast, she used to wash and put 2 eggs per family member in the boiling pot of dudh-patti. It was followed by preparations of lentils for afternoon as there were no pressure cookers. A lota full of water was kept over the balti, which provided enough weight that the pressure doesn’t escape and was later added to the lentil when required to maintain the consistency. Once the fire in the chullah simmered down or just the embers remained, a pudding-like gooey desert was kept to be prepared. Again, simplicity at its best, roughly beaten eggs, butter, sugar and cardamom were kept on the embers. My mother recalls how this is the best pudding she has ever relished, especially when compared to desserts baked in an electric oven.

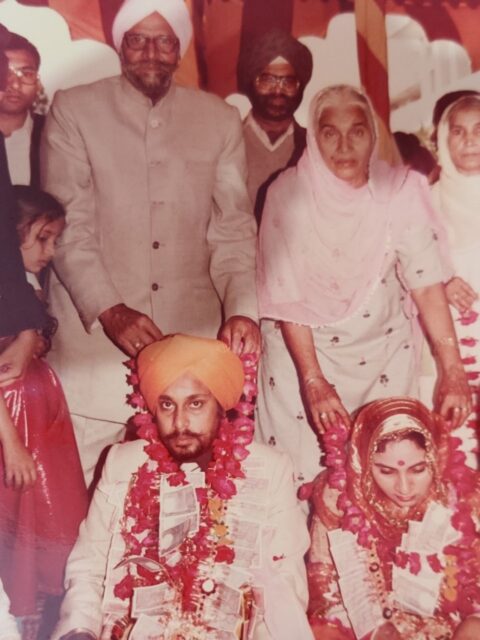

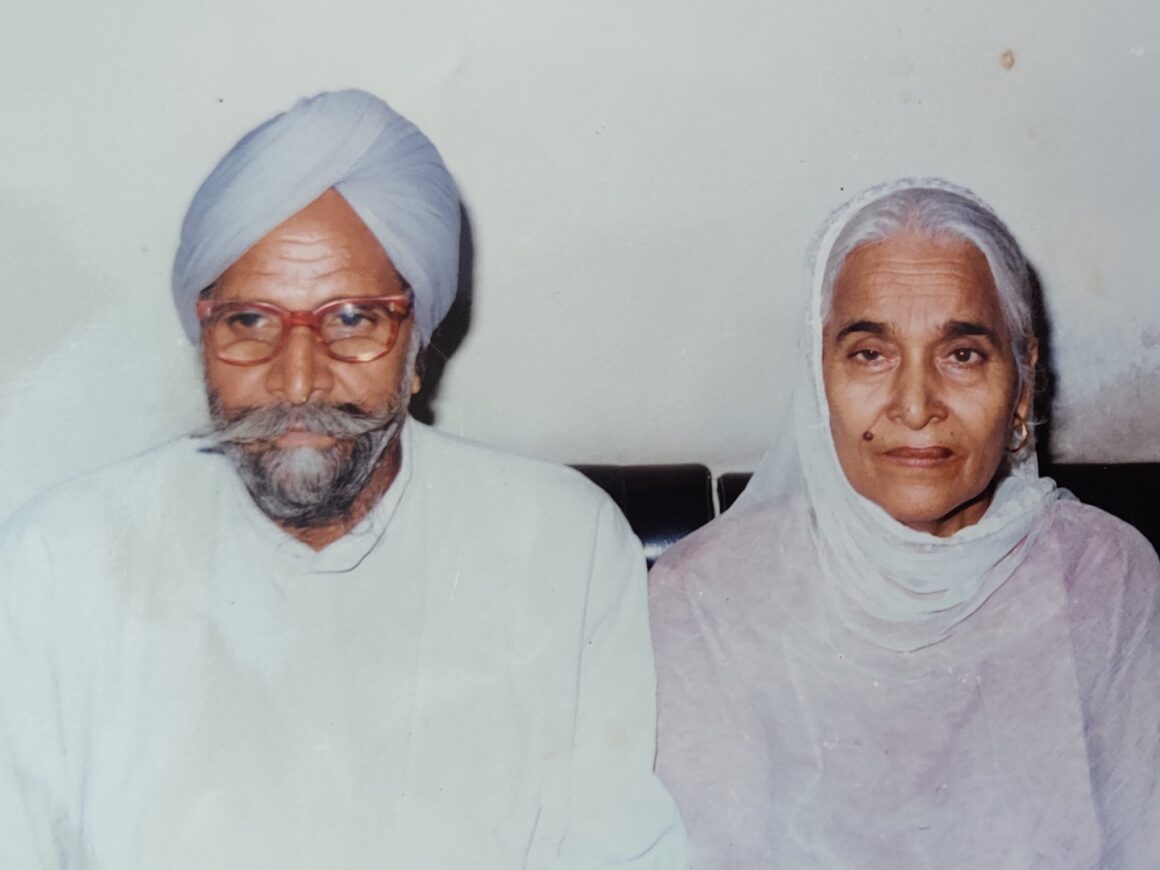

We are probably now living with the last generation of refugees who migrated to India. So here is my attempt to resurrect one of the simple, flavorful preparations of the pre-partition era, chhitt and awale di sabzi, before they vanish. It will not be an exaggeration if both are called close cousins of each other as they look alike and have milk as their common major ingredient. What is intriguing here how milk and awale (also spelled as amla), Indian gooseberries make it into the same dish. Amla, a rich source of vitamin C is the best ingredient for the milk to curdle. This is my mother’s recipe, who is the last person to have learned the recipe from her mother who was 16 years old when she fled to India from Pakistan, the only one to survive the massacre her entire family had to face.

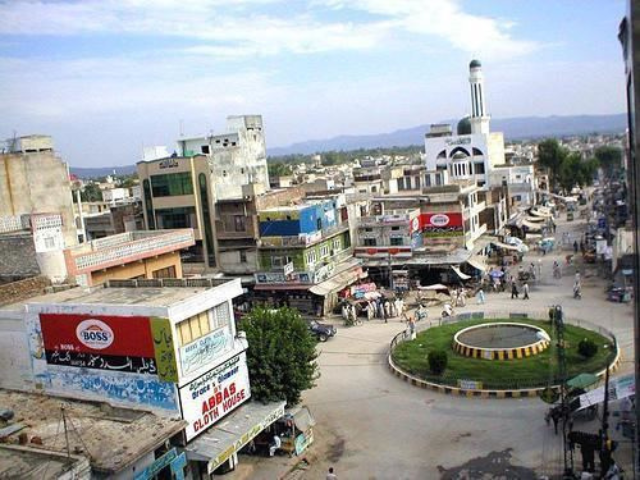

At that age, she was cooking all three meals for her family and thus carried her heirloom recipes with her. She belonged to a place called Campbelpur named after the British Field Marshall Sir Colin Campbel , a place she would pronounce as Camelpur. (She could not read or write). In 1978, the town was again renamed as Attock.

Google Images

As mentioned earlier, chhitt, more precisely called adrakh di chhitt is a comfort meal for winters. Fresh and roughly pounded paste of ginger, garlic and almonds is fried in generous amount of homemade ghee. This fills the kitchen with a tempting aroma. Once the smell of raw garlic subsides, turmeric and crushed black pepper are added to it and the flame is reduced. When the turmeric is cooked, a bowlful of water is added and the ginger and garlic is boiled in this water. As the water reduces to half, full boiled milk is added to it and the flame is turned off immediately so that the milk doesn’t curdle. The ghee oozes out from the masala and forms the top layer of the chhitt. Chhitt is mostly eaten like a warm soup in harsh winters, often accompanied by a phulka which is crushed and dipped in the bowl of chhitt itself. The pepper and ginger soothe the throat in the biting winters of north India. I have not added precise measurements to the recipe, it is best made by applying the theory ofandaaz or intuitive cooking.

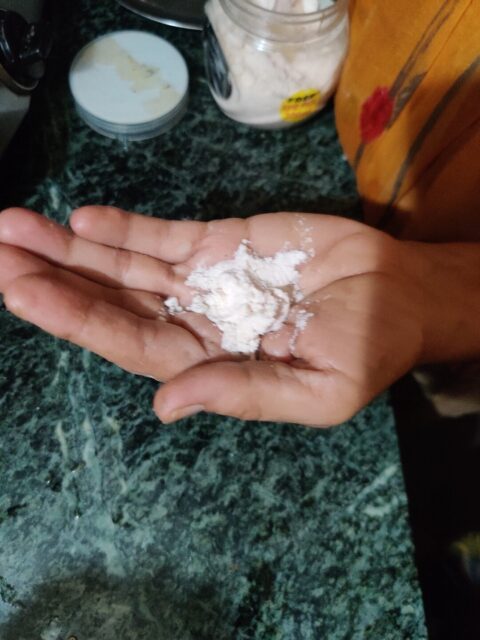

Awale di sabzi, on the other hand is the milder version of chhitt and is its summer counterpart as amla has a cooling effect on the body. To make awale di sabzi, a handful of dried amla is taken and thoroughly washed. My grandmother insisted on washing them 40 times to remove dirt and excess sourness and bitterness. Amla is then soaked for 5-6 hours.

Later, a medium sized potato and the amla are boiled together. Since amla are already soaked, both get boiled at almost the same time. Next, a ladleful of ghee is added to the kadhai. Once it heats up, amla is fried in it for 3-4 minutes.

The potato is peeled, cut into pieces is added, followed by a freshly ground paste of roughly pounded cumin, coriander seeds thrice the amount of cumin and garlic greens. All of this is fried in ghee at a simmered flame.

Next, she adds turmeric, red chili powder, black pepper and a bowlful of water to deglaze the kadhai.

Parallelly, in another pan, milk is brought to a roaring boil and added to the kadhai and the flame is turned off. However, there are precautions to be taken like: add salt just before consuming, consume soon, as keeping it for very long can cause curdling. Also, reheating should be avoided.

Although, the modern version of the dish has a modern twist, my mother adds a pinch of baking soda both when adding water in the kadhai as well as to the milk in the pan. This saves the milk from curdling on high heat in the presence of amla. However, I believe this is the reason nani insisted on washing the amlas 40 times!

The taste is certainly unique with slight bitterness of amla, freshness of garlic greens against the sweetness of milk and occasional bites of coarsely pounded coriander seeds and potatoes.It is also best served with thin phulkas.

These recipes are simple for us but from the ones whom we have inherited them, it was a way of living and practicing their ethnicity. No matter how mundane these foodways appear, they belong to those who were uprooted from their places of origin and thus, it becomes our duty to share them and give them their due credit.

Navreet Kaur is a PhD candidate at Institute of Ethnic Studies (KITA) at The National University of Malaysia (UKM). Her area of interest is Anthropology of Food in India and Ethnic Foods of India. Her work can be accessed with the ORCID id 0000-0002-8039-7954.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.