Kirat karna ; vand chhakna te Naam japna

[ Earn.. (a) living by.. (doing) labour, share it with others, and repeat the name of Almighty. ]

I’ve always wondered what is so special about partaking in the langar at Harmandir Sahib, or any sacramental community eating for that matter. I’ve experienced it many times as a child, when you do the things your parents do, when you don’t question faith or whatever it is that people go to these places in search of.

This time when I travelled to Amritsar, my uncle insisted that I must savour the guru ka langar once, whether or not I do anything else there. I dislike being pushed around in crowded places, I dislike walking barefoot, I dislike too much heat, I dislike standing in queues for long. What could possibly be gratifying about going through all that for a meal?

The morning rays ricocheted off the milky flooring, making everyone squint. Subject to profuse scrubbing, the marble had renounced most of its texture. It felt hot and soft against the soles. Baisakhi revelry was on in full swing and a sense of contagious hurriedness (an involuntary Indian tendency at religious shrines that amplifies during festivities) had permeated the temple premises.

Across the Indian subcontinent, Vaisakhi or Baisakhi, with regionally diverse names and consecutive dates, is celebrated as the spring harvest festival and solar new year. It is a day of offering gratitude to nature, for its abundance, and to the farmers who toil to feed us. In the Punjab region, this day marks the ripening of the rabi crop. It also commemorates the coronation of the tenth and last Sikh Guru, Guru Gobind Singh and the inception of Panth Khalsa (the Order of the Pure Ones), to defend religious rights. Community cooking, feeding the indigent, sharing food and singing hymns are at the heart of every celebration in the region.

Everyone seemed to be walking at a uniformly swift pace. Just at the brink of collision, the crowd would mechanically change direction, like an army of ants, repelling each other’s path. Of course, this harmonious movement switched into an impatient frenzy, as the throng approached the shrine. People slid through, elbowed through and requested their way through to make it first.

To our right was the way to the main shrine and to our left was the staircase leading to the sacred langar hall (the communal free meal service). Along the staircase, volunteers were handing out plates to an unending queue of hungry visitors.

The cooking process is branched out to several rooms and spaces around the hall. The mise en place pretty much happens in the passageways outside the hall where devotees sit around in groups, peeling and chopping vegetables.

We scurried through the crowd and slid into one imperceptible room, where the rotis were being made. Roti or phulka (hot puffed up roti), the staple bread across northern India, is usually made by hand. Wheat flour is kneaded with water, a small dough ball is rolled into a thin circular disc, baked on a flat iron pan and finally tossed on fire a few times so it puffs up and is slightly charred.

Of course, here the phulkas were being made at a prodigious scale. Maybe a score in a minute end-to-end. There is an entire section where volunteers can sit down and prepare rotis by hand. But, in these langar halls over 100,000 people are fed in a day. So, the whole process from kneading the dough to achieving puffy phulkas is also carried out on state-of-the- art machines. Barring one step – slathering them with ghee.

I choose to believe it’s because this step requires unmitigated love. Baskets of piping hot phulkas are handed to devotees who sit in circles and sing spiritual chants as they unsparingly apply ghee. Adding a generous dollop of ghee to another’s meal is a symbolic representation of affection across the Indian subcontinent.

The Guru Granth Sahib too, has a verse dedicated to the sanctity of ghee.

[ ann dayvtaa paanee dayvtaa baisantar dayvtaa loon panjvaa paa-i-aa ghirat ; taa ho-aa paak pavit. ]

The grain is sacred, the water is sacred; the fire and salt are sacred as well; when the fifth thing, the ghee, is added, then the food becomes pure and sanctified.

The custodians of the gurudwara kitchens are unperturbed by one’s enthusiasm to document everything on camera. Tejinder, a young supervisor of the roti machine walked around with us, hospitably explaining the process as we went about clicking pictures rather obsessively.

The elderly smiled at us with what I reckon was pity towards our vanity and politely encouraged, “bete, sewa bhi karo, sewa bhi karo,” (child, you must partake in some service too). Cutting vegetables, continuously stirring the cauldrons, serving food and water, mopping the floor – one can choose to be involved in any service or just walk around and absorb the potential of synchronized compassion.

We sat down with the ghee and absorbed the magnanimous impact of community cooking. And this was just on a diminutive scale, for a few minutes.

We dipped makeshift handheld mops – made of wood and cotton cloth – into large bowls filled with pure desi ghee and started applying it generously and leisurely onto the phulkas. One gentleman who had been observing each one of us novices attending to one roti for ten seconds advised, “bete, aise toh sab bhooke reh jaenge, jaldi jaldi haath chalao,” (kids, if you continue at this pace, everyone will go hungry today, work your hands faster). We took a quick look around and realised that everything was happening at lightning speed. The forethought that there were hungry people swarming in all day, and there can be no room for compromise or delay, was programmed into everyone volunteering. And yet, nothing seemed anarchic. It was a well-oiled assembly line, fuelled by a shared sense of responsibility.

The free community kitchen concept is one of the main pillars of Sikhism. It was started 500 years ago by Guru Nanak Dev ji in 15th century Punjab and even today, not only in Gurudwaras but in areas of riots, distress and famine, Sikhs are often the first to set up langars and pyaus (makeshift setups that offer drinking water and chabeel – a rose flavoured summer drink) to aid people.

It is said that Guru Nanak’s father once gave him 20 rupees to set up a business. He was on his way to the market to make purchases for the same, when he saw some hungry saints singing hymns. He spent the 20 rupees, a big amount back then, to feed the sadhus. Since then, this tradition became a part of Sikhism.

Guru Nanak Dev ji’s thought behind starting the langar was to encourage people from all walks of life to sit on the floor and eat together.

The langar is a thriving manifestation of generosity and an empathetic endeavour to inspire hope, and it happens at an unfathomable scale in Amritsar.

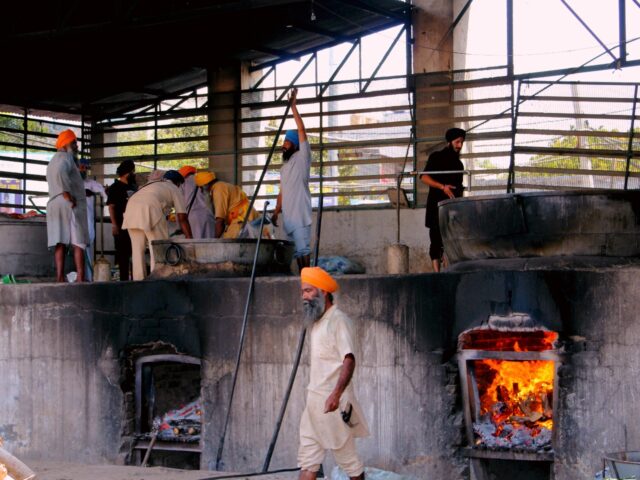

The food here, is prepared and served by a community of people, who arrive with this profound desire to harness a sense of solidarity. We entered an indoor kitchen where side dishes required in ‘smaller’ quantities are prepared. This would usually be up to 2 quintals (200 kg) each, of sabzi (dry vegetables), chai and pakoras (fritters). In the outdoor kitchen, 4 quintals of kheer (a sweet pudding made of milk, rice and sugar) and dal (mung bean lentils), were simmering in the world’s largest kadahas (vats). This process goes on day and night, non-stop, as the langar sewa feeds people round the clock. On festivals, these quantities can go up to ten-fold.

Thousands of devotees donate wheat, rice, lentils, vegetables and milk. In fact, for Vaisakhi, many dairy farmers from nearby villages had brought milk from their homes, as an offering.

From cooking and serving the food to washing utensils and keeping the temple premises spotless – all of it is seamlessly managed and pulled off with tact, entirely by volunteers.

Beyond question, it must be faith that makes such an inconceivably massive, unlimited service possible. But here’s something to introspect. This is food we’re talking about. Food that hundreds of thousands of people eat on any given day. It would be unnerving to think of everything that could possibly go wrong in such an enormous, autonomous kitchen. Then why hasn’t it, ever? Undeniably, each person has the best intent at heart, because the purpose behind coming here is to serve khaalis (simple and pure) food. However, this prodigal spectacle also serves as a fine example of nimble entrepreneurship.

It seems as though the food is designed, bearing in mind, that langar cooking is participatory. Round the clock, devotees swarm in and out of the gurudwara kitchens. Complex recipes would interfere with the agility and fluid nature of the process. Interestingly, the classics of the Darbar Sahib kitchens, like dal and kheer, keep getting better with continuous stirring. Hours of cooking tends to enhance the dish without burning it and allows for many devotees to continue the relay.

Satwinder Singh ji, the head of the Darbar Sahib Kitchen, fondly introduced to us as ‘master-chef’ by the staff, offered us some fresh pakoras and tea, and took us through the day’s menu, explaining the science behind it. He shared that the same batch of dal, for instance, is cooked from midnight to 5 pm the next day. Bulk cooking can often jeopardize taste. Slow cooking draws out the natural flavour from the produce and evens out the seasoning, without leaving the food too bland or spicy, making it enjoyable and suitable for people of all ages.

Dal and sabzi (vegetables) prepared with onions, garlic, ginger and spices like turmeric, chilli and salt; rotis (bread) smeared with ghee; kheer (dessert) made of rice, milk and sugar, altogether make for a perfectly balanced, nutrient-rich meal.

Partaking in the langar is not contingent on one’s religion. It isn’t mandatory to even visit the shrine. If you’re hungry, you will be fed. The only protocol is to be respectful and cover your head while you’re inside the temple gates. We decided to brave the serpentine queue and come back later to eat. When you finally make it inside the temple after hours of wait on festivals like Gurpurab or Baisakhi, you get but a few seconds near the shrine, the temple staff repeatedly instructing you to keep moving.

What is truly exceptional to watch, is that, until an individual enters that door, there is a competitive mayhem. But the temperament of the crowd changes, en masse, the moment it nears the Guru Granth Sahib (the holy scripture, which the Sikhs regard as their living guru). The number of people around, suddenly doesn’t seem to rile anyone, like obedient students, under observation, on their best behaviour.

We left with a heart full of contentment and a hand full of karah prasad (holy sweet made of whole wheat flour, sugar, ghee and water in equal proportions). Most of us have often dared to ask for the karah prasad at least twice, often gobbling it up and standing in queue again to eat more!

At the langar, we waited and waited for our turn. As soon as we were allowed to proceed, the crowd sprinted towards the hall. Walking barefoot in the heat or cold, urges you to acknowledge your privilege. And the fact that no matter who you are, you must sit on the same floor with everyone, and reach out with your palms to accept the roti, shows that food has to be respected here.

We sat down with our plates, tired and hungry. The good Samaritans came with buckets full of dal, matar paneer (green peas and cottage cheese curry) and kheer. Big water canisters wheeled by, filling our bowls with drinking water. When you work hard and play your part in this grand project, finally taking a moment to rest and cherish the meal can be a truly rewarding experience.

I would be remiss to not mention here, that this whole system functions without single use plastic. There is a conscious effort to minimize any harm to the planet, and for that purpose, only reusable and biodegradable materials are used. Looking at this living, successful example of what a sustainable society might look like, galvanizes you and inculcates a sense of social responsibility in you. Something this colossal can survive only on such energy. It seems ironic that one would come searching for peace to one of the most crowded establishments. But there’s no better way to describe it. This is, indeed, the most beautiful, synchronous occurrence of chaos and serenity.

The melodious sound of ardas (prayer songs), the calm of rippling water, the discordant babbling of people and the distant clanking of steel plates, played around us. We sat by the pond, watching the sun which had begun to set now, rendering a somewhat celestial brilliance to the golden edifice.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.