The drive from Dimapur to Kohima is worth describing for several reasons. The view is quite serene. Almost too serene if it weren’t for the unwelcoming roads. The sky is one shade of unbelievable blue. Made believable by the dust from the ground chronically disturbing your view and lungs.

At some very abrupt corners along the curving roads are some shacks selling tree tomatoes, spring garlic, Naga chillies, some wild herbs foraged from the hill forests. And pineapples. The best pineapples, which are cut up and served on sticks like juicy ice pops, only superlatively better. The kind one does never forget.

After three hours of back breaking, breath-taking (for the eyes and lungs) and pineapple eating, we reached Kohima.

Dimori Cove is a charming little café and boutique resort, with a cheerful fireplace and the most luscious honey cake.

We sat out at one of the patio tables for lunch, the Japfu peak towering over us, peering into our disproportionate order of some very tantalizing Indian-Chinese food.

At 5 pm, the sky turned sooty and our toes started to stiffen. We sat by the fireplace, demolishing the honey cake and braced ourselves for a cold early morning. The night seemed to be getting colder by the second. I made a mental note to wake up 30 minutes ahead of time to switch on the geyser, and tucked in.

There was a power cut. One socket seemed to be working. I plugged in the electric kettle and started collecting hot water in a bucket. Only, the water would turn cold by the time I added more. After a half bucket, lukewarm, killjoy of a shower, we grabbed a quick breakfast and started our trek.

The Hornbill festival unlike how one would imagine, does not happen on one large field. It happens at the Naga Heritage Village in Kisama which is a hilly terrain. It is spread out across the hill, making it somewhat of a tiring but obsessive culture hunt.

Hornbill isn’t the only highlight worth visiting the state for. But, if you happen to visit in the beginning of December and are pressed for time, this is the one place you should choose. It opens a window into the cultural diaspora of Nagaland, its people, their energy, the clothes, the food, the stereotypes, the perceptions…

Sweet Sixteen

After a thirty-minute walk uphill we started to hear some distant brouhaha. Puffs of dust were swelling up in several spots. Smoke from woodfire seemed to be rising, possibly from provisional kitchenettes. We passed the sixteen ‘Morungs’ (dormitories) looking for a starting point. Khiamniungan Morung, Pochury Morung, Garo, Angami, Chakhesang, Rengma, Lotha, Ao, Sangtam, Yimchungru, Konyak, Phom, Cham, Yimchunger and Sumi Morung.

There were general cultural descriptions on boards near each morung. About Khimniungan weavers, renowned for their intricate designs and their bright red and bright deep blue traditional dresses. About the Garo people – the harvesters who do not use any agricultural products before expressing gratitude to the goddess of fertility.

The Konyaks – who are said to have been the most successful tribe in preserving ancient traditions. They’re proficient in woodcraft and weaponry. We met some elders who had face tattoos that symbolize their participation in the practice of headhunting.

Most had descriptions of major festivals celebrated in the anticipation of a good harvest season; of merrymaking, praying, singing and dancing.

Then we came across one board describing a collective tribe called Kacharis. “A good number of tribal communities inhabiting different parts of Northeast India are called Kacharis. They are generally simple, docile, good-natured and peace-loving people.”

There seemed to be some persistent effort through all forms of communication to ‘humanize’ themselves. There was an accurate understanding of common perceptions that need to be rectified.

Each tribe’s morung was a display house of sorts, with their cuisine and crafts demonstrated inside and around the morung. Men and women dressed in their vibrant handlooms, sang and danced energetically. There were even some lively enactments of tribal warrior dances, using spears and animated body movements.

Tourists hovered over the performers, taking pictures with them and making no attempt to converse.

We approached some young performers for a chat. One of them grinningly said, “We’re all college students you know. We come here to participate in the festival. Some people come here thinking we all live in jungles, hunt and wear these clothes all the time. Funny, nah?”

The Naga Couturiers

Reds, blues, blacks and whites with occasional pops of sunny yellow and leaf green. These colours dominate the fashion contexture of Nagaland. Sarees, coats, shawls and upholstery in traditional Naga weaves were showcased on racks, mannequins and enthusiastic sellers.

The Naga design philosophy conveys a sense of bold minimalism. All Naga textiles are woven on the loin loom – the most ancient loom and all designs are solely memory based. Structured fabrics in solid colours with neat, geometric patterns are its fundamental elements. Naga artisans and designers are a different version of minimalists. They make the best use whatever raw material nature surrounds them with and manage to come up with ingenious creations. Trimmings of vibrant tassels, conch shells, and beads are all part of their definition of the concept.

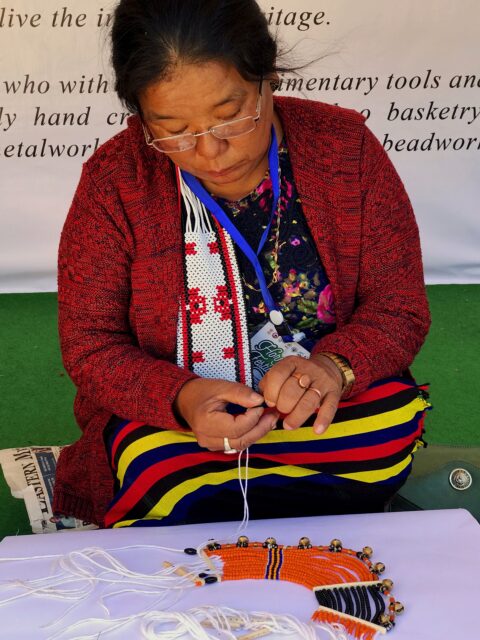

We met some artisans who had no avantgarde appliances. They were constructing chic basket bags, clay pots and jewellery with their bare hands and a few bamboo tools.

The Department of Women Resource Development and the North Eastern Network are the trail-blazing organisations bringing women artisans and designers together.

These organisations are dedicated to reviving sustainable traditions, empowering women and creating a space for constant design thinking and innovation. Each piece under their umbrella is on-trend and exclusive.

Like the Queen’s Bag. The Anghya Nyekok, (which literally translates to queen’s bag), is a speciality of the Konyak tribe. It has evolved with time in its significance and design. What used to be a bag reserved for royalty, has evolved into a statement. Today, it is a symbol of self-sustenance, innovation and education.

In the Naga culture, colour combinations and weaving patterns are tribe-specific and often denote one’s achievements and social standing. Like the spear motif is used by Chakhesang women to illustrate valour. The elephant motif is woven into special shawls as a symbol of aristocracy.

One standout brand was Chizami Weaves. Their upholstery pieces in monochromatic tones with sharp structured patterns had the versatility to complement any interior aesthetic.

And the Chakhesang shawl. Typically, black with yellow or red highlights, this Naga shawl can singlehandedly shield you from the piercing north-eastern winds. Plus, it does the work of a blanket should you find yourself too comfortable to move once you’re wrapped in it.

An Endangered Craft

The Chakhesang are known for their creativity and deftness. What they’re also known for, is the thebvora. Whether or not you’re into muted tones, the thebvora will draw you to it. Native to the Leshemi village, this fabric of many talents is made from the stem of the stinging nettle plant.

First, stinging nettle is foraged once a year, from the hill forests. The harvested plant is cut and left to be cured for about five days, so the bark strips away from the stalk. The nettle is then further peeled into fine strands and boiled in wood ash.

Once ready, it is pulled out from the vessel and macerated with a heavy wooden beater, twenty to thirty times over a stone surface.

It is rendered a rice starch treatment to bleach the fibres and make it stiff for warping , then cured in the sun. The nettle hanks are finally reeled and hand spun into balls for warping, to weave the thebvora. The forest to fabric journey of this wild plant that predates cotton is completely sustainable and has zero carbon footprint.

Back in the day, thebvora was a common textile for the Chakhesang. It was used as a shawl, a blanket, bedding or used for carrying paddy when fashioned into a sack.

Today, it has been categorised as an endangered craft. Mostly because the laborious process and precision involved in manufacturing this fabric is no mean feat!

The Chakhesang Women Welfare Society (CWWS), Pfutsero (a town in the Phek district) has intervened to experiment with finer textures and new silhouettes. Product innovation and generating awareness about the proficiency required has managed to generate the headlining this textile deserves.

We stood there watching plant stalk metamorphose into royal fabric. Thebvora has an excellent finish, is durable and harmless. It has a shifty fall and would perform well as a winter wrap, sofa throw, nook blanket. The possibilities are rife.

There is a proper recipe, that is both ingredient and time sensitive, to be followed to prepare it. In every sense, hand crafting such exclusive natural fashion is tantamount to a legendary chef’s signature dish. And by that analogy, this dish is Dan Barber level.

Saucy Joe

If there’s one specie Nagaland can never be deprived of, it is that of smashingly flavourful herbs. Markets, mountains and morungs, everywhere, the Naga people have transformed dishes with just herbs.

We found a few being used in the many cauldrons bubbling away behind the morungs. There was mothi (Sichuan pepper), oshuvu (a wild weed with a strong flavour resembling coriander) and of course the Naga mircha (chillies).

In India, wherever one travels, it is crucial to scour for the best chutneys. In Nagaland, even more so.

We trudged along the periphery of the Heritage Village and chanced upon Saucy Joe’s Sauces. This Kiosk had an archness to it. Beautiful packaging, distinct visual merchandising and the striking colours, telling of their piquancy.

The brain behind these seemingly promising sauces, was coyly standing by the side. Chef Joel Basumatari, a name well-known and respected among the Nagaland culinarians, brought into our lives, the Naga basil sauce.

Now, when normally speaking of chutneys, I tend to imagine big jars, because I consume chutneys like gravies. These were small handy bottles, the kind you can carry around in purses, in case your dinner needs salvaging.

We sampled the basil sauce. Something happened. My ears popped. It was like fireworks. Sharp, hot, astonishingly fresh and very citrusy. It looked and tasted like it had just been plucked, ground and bottled.

Chef Joel informed us that his recipe used the Naga green lemon basil, another potent treasure from the region’s herbage. Hence the electrifying zing.

He encouraged us to go for his Naga King Chilli Sauce next. The bottle was giving off an intimidating at-your-own-risk vibe.

Hearts beating in our throats, we tasted a tiny bit. My whole body warmed up. An explosion happened somewhere at the back of my head, leaving me misty eyed. Sheer thrill.

Somewhere, in another corner of Kisama, the Naga Chilli Eating Competition did an eyeroll.

Honey, It’s a Bittersweet Story

Characteristically, honey is expected to be sweet. It is also expected to be viscous, folding into heavy layers as it drips.

Of the four types found in Nagaland, not one honey can be defined as outright sweet. And technically, raw, unprocessed honey, which is said to be the most beneficial, is typically runny.

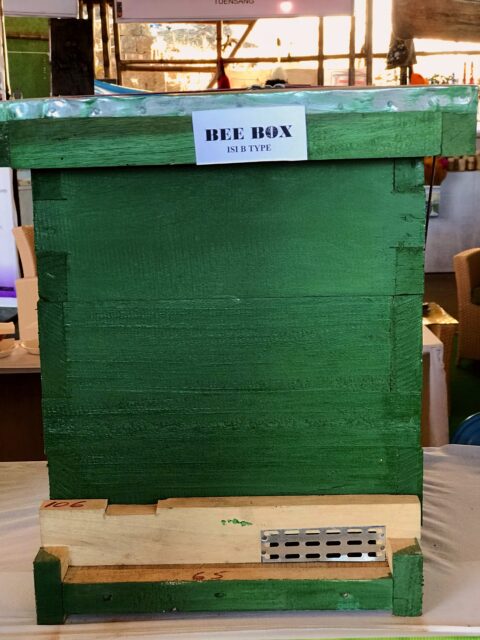

Neilazono, a representative of the Nagaland Beekeeping and Honey Mission educated us about the different types of bees and their produce.

Every conservationist, apiarist and bee lover associated with the mission is extremely impassioned about protecting the bees. They work towards building a sustainable, stable livelihood in consonance with nature.

The cheruthen honey is made by small stingless bees and has a sweet and sour profile with a lemony undertone. This variety has many curative properties and is often used as a medicine.

The flowers of such therapeutic shrubs are usually tiny so the stingless bees are the only ones able to extract nectar from them.

It helps heal cuts and burns, treats colds and upper respiratory discomfort and can be used as a remedy for infections and insect bites. We’re told it works great as a tangy drizzle on fresh salads too.

The honey produced by the giant rock bee has a deep burnished hue and a pronounced bitter taste. To be able to appreciate this honey, one must first unlearn the notion that honey is synonymous with sweetness. Once you taste this a few times, you start to understand its potential – spice rubs and cocktail mixes to begin with!

Black honey, produced by Asian bee (Apis Cerana) is a sweeter variety with a robust earthy flavour and is the colour of liquorice. We’d say it works well with floral and herbal teas.

And there’s another honey, the familiar variety, also produced by the Asian bee, which has a floral, ambrosial taste. This is the most commonly consumed all-purpose honey.

Ethically, sustainably produced honey doesn’t come cheap, and the mission attempts to create awareness about the work that goes into it.

Spend some time at the beekeeping mission and you will never look at honey as just another sweetener again.

You will learn that honey bees never sleep. They just stay inert at night and preserve their energy for the next day.

And that the average worker bee produces only about 1/12th teaspoon of honey in her lifetime.

Sweet?

From the Ao Beer Barrels

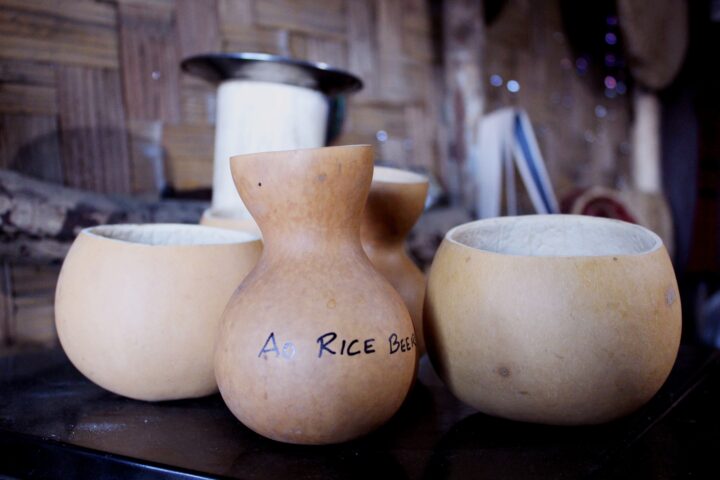

Kiala belongs to the Ao tribe. The tribe that makes the best rice beer, we’ve heard.

It’s a process she utterly enjoys and takes great pride in. When we met her, she was busy getting a fresh batch ready. She scooped up a spoonful of the fermented rice and fed it to us.

It had a bold, tart introduction followed by a sweet, calm impression from the rice.

Kiala is a warm, cheery soul. The type of person whose smile evokes yours. But she doesn’t particularly enjoy explaining the whole process. For her it is muscle memory, and to recite it with every precise detail interrupts her rhythm.

So, we observed, made some notes and called one dear friend from the Ao tribe, Sentila Imsong, who patiently helped us understand the process.

She notes, “the one important ingredient that is required for making rice beer is peyazu (Ao), the fermenting agent.

To Make peyazu, we first soak the rice overnight. The water is then drained out till it is completely dry and the rice is sun dried.

Next, we take the rice and pea aubergine leaves and pound it together into a powder. This is done using a large wooden mortar and pestle. Some water is added to the powder to make a semi soft dough. Cookie sized cakes are made from this dough and the peyazu is either dried under the sun or near the fireplace.

To make the rice beer, the rice is first steam cooked normally. Local varieties of sticky rice (similar to jasmine and sushi rice) make the best beers. The cooked rice is spread out on a pakti (flat mat made of bamboo). Once the rice comes to a warm body temperature, the peyazu is crushed and properly mixed into it. The mixture is then transferred into a molok (bamboo basket) underlined and covered with a mongo tu (banana leaf). The molok is kept securely in one corner of the kitchen away from any heat or odorous food for 3-4 days. When the beer is ready, it releases a distinct sweet smell and that’s when we open the basket.

There are two variants of this beer. The clear watery form called mejamtzu which comes from following this process. Then there is the Milky form, peyajok, which is made by stirring some of the fermented rice into the liquid, making it thicker and changing its texture.”

Pro tip: If you ever happen to come across a Kiala crafting rice beer, do not disturb her process. Observe and taste.

Axone, From the Epiglottis

We met Khetovi and Agapeli at the Sumi morung. At the time, Khetovi was studying Political Science and Agapeli was to graduate in English Literature.

Agapeli had an endearing, interesting habit of describing food in phonetics. Perfect when learning about axone, I thought.

Pointing to her epiglottis she said,” we speak from here na, a-kho-ne,” repeating the ‘kh’ sound again and again until we practiced and got it right.

While taking us through some local spices they regularly cook with, she brought out some anise seeds and vocalised, “when you eat this, you get a ‘znnng’.”

Khetovi taught us a lot about Naga dishes and spices. He detailed out the process of making axone.

Axone is made by fermenting soya bean. Ripened beans are soaked, then boiled. Once soft but intact, they’re strained and mashed gently by hand. The mash is wrapped up in a mongo tu (banana leaf) and kept above the fireplace on the akhache (suspended bamboo grill) for a week.

Once the protein ferments it releases a weighty, pungent smell and its colour darkens, making it ready for use.

On the akhache, chunks of pork were being smoked for preparing the signature dish of the Sumi tribe, smoked pork with axone.

When first introduced to axone, one can feel far removed from their comfort zone and experience a flighty headrush. It does take some getting used to. But those who love it, come looking for the finest axone, made using beans sourced from colder, higher hills. Preferably the one placed undisturbed above the fire.

Khetovi told us that when they go to college, their mums give them big jars of pickles, and add a little axone to preserve them for longer. The passion for pickles in Khetovi’s eyes mirrored mine.

Produce! Produce! Produce!

Have you ever tasted a tree tomato? A beautiful, tangy fruit, high in pectin, which makes it perfect for chutneys and jams with a long shelf-life. These folks know how to whip up a mean tamarillo chutney.

The winter yield is particularly exciting. Khuvie, their indigenous garlic is brimming with flavour and is the starlet of the tamarillo chutney. Lush, blooming cabbage, earthy tapiocas and meaty pumpkins sitting in the kitchen gardens, waiting to be turned into soups and suppers.

Yes, there’s pork and yam and bamboo. There’s also all of this and then a bushel, of produce and possibilities.

Remember the pineapples? The most saccharine ones, packed with potential. They remind you of everything you could create with great fruit. Plus, the chillies of course. Wouldn’t they work great together?

We realised we had missed such valuable tasting on our way up, when Azhabu, our friend driving us back to Dimapur, casually spoke about the exquisite produce. So, we had to stop for fruit.

Basking in the Kohima winter sun and enjoying a Khasi mandarin is a story in itself. One that you must go there and write for yourself.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.