Foreword

“Ooh helloooo!” Kurush called out to the bird singing on the tree outside the patio of the Olde Bangalore resort where we were filming Bombay Bygones.

“Brahmani kite.”

“Oh sorry, not allowed to call them Brahmani kites now. But that’s what we used to call them.”

I wasn’t sure if it was the coffee or just Kurush Dalal being himself, but he seemed to be engaging with everyone and everything around him. Bird, human and food alike.

His energy shifted from riotously funny to grave to awe inspiring in split seconds without ever dropping.

You look at the countless praises for Kurush on social media or hear about him when you meet a common friend, each one of them will tell you what a great teacher he is, what a gifted storyteller he is and how full of life he is, and that is all true. But, there’s one thing that makes Kurush awfully precious. It is his superlative ability to make the other person in a conversation feel like the more important one in the room despite the fact that he has an endless string of stories to spin.

In one afternoon, he took me from Bombay to Rajasthan and further north, making a whistle-stop visit to Dehradun. By the time I realised how far I had travelled, we had sailed across the European seas and come back home.

On this wool-gathering voyage, I guffawed, gasped and got gooseflesh. For the first time in years, I did not realise that I hadn’t looked at my phone or checked my email during work hours.

I returned rich, with a bag full of stories wanting to share them all with the world. The camera roll didn’t suffice but we managed to get at least a few of them on record. I’ve listened to each one of these five stories over and over again. Hearing them repeatedly has somehow made me a spectator inside the stories, which feels ridiculously cool, like some kind of trans-temporal travel.

Kurush’s stories often talk of his family and how anyone who entered their house would never leave without a meal and a story. As a storyteller that’s exactly what he (inadvertently) does for his listeners. Once you’re sitting around him and the minute that story begins, it doesn’t matter who you are or where you’re from, you belong.

Ramya G. Sri – Editor, Bruite Magazine

Story 1 – Gadheri Nu Doodh

Mumbai from the 70s and 80s was a very different world from the world we see today. Imagine a city where the cacophony of Zomato and Swiggy delivery bikes is replaced by the rhythmic jingles of bells. A city where the rapidity of today’s life is replaced by a languid pace, where every moment was savoured, not rushed through.

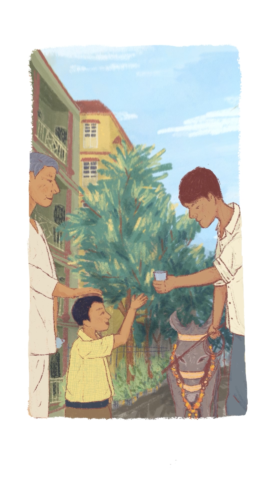

One such vivid memory from this bygone era is intricately tied to the city’s foodscape. A peculiar ailment, the whooping cough, was rampant then. But Mumbai, with its myriad of cultures and traditions, had its own unique remedy – the milk of a jenny, the female donkey. It wasn’t uncommon to hear the harmonious chime of bells, accompanied by the melodic call of “Gadheri Nu Doodh”, echoing through the streets. Vendors, with their adorned jennies, would parade down the lanes, offering this sweet elixir to those in need.

I recall a time from my youth when a persistent cough had me in its grip. My grandfather, with his repository of traditional wisdom, was convinced it was the notorious whooping cough. On hearing the familiar call of the donkey milk vendor, he’d beckon him. Together, we’d descend with a bottle of water and a glass. The ritual was meticulous: the jenny’s udders were to be cleansed with clean water from the house before the milking began. The yield? A shot glass filled with this sweet nectar. No sugar, just the natural sweetness of the milk. This became a routine, a series of days where the vendor would faithfully arrive, and I’d have my daily dose of the remedy.

Fast forward to today, and it’s intriguing how the wheel of time has turned. The once-forgotten donkey milk is now under the scientific lens, with its curative properties being heralded. In places like Gujarat, donkeys and camels are being reared specifically for their milk. It’s almost poetic, how after half a century, we find ourselves gravitating back to the wisdom of our ancestors, realising the truth in those ‘Dadi Ma ke Nuskhe‘.

Story 2 – Doodh Na Puff

One of the captivating aspects of South Bombay was its audioscape. The distinct audiosphere was a testament to life there, influenced by the fact that every house had a balcony facing the main road. The relatively shorter buildings and the vendors weaving through the lanes, hawking their wares, contributed to the heritage sounds of the area. Growing up, I fondly remember the chime of the Rajabai tower clock every quarter hour. Unless traffic was particularly heavy, its sound reached my home. Today, I’m uncertain if it still chimes every quarter hour, for the modern trappings of air conditioning, stainless steel, and glass have transformed the city’s soundscape. The calls of hawkers, once a familiar tune, now seem lost in today’s world.

In the winters, especially in areas populated by Parsis, a unique vendor would make his rounds: the Doodh Na Puff Walo. Doodh Na Puff, a Parsi delicacy, bears some resemblance to ‘malaiyo’ and ‘Daulat Ki Chaat’, though they aren’t identical. The process involves reducing a generous amount of buffalo milk by about 50%, seasoning it with elaichi and a touch of sugar, and then letting it cool overnight on a terrace. The dew, believed to play a role, would fall onto it. While I’m sceptical about the amount of dew Mumbai receives, it was considered essential. The milk was then frothed using a hand churn frother and collected in glasses. These glasses were placed in a large wooden crate and carried around with the vendor shouting “Doodh Na Puff“. Accompanying this was ‘Kharia Ni Jelly‘, a spicy jelly made from goat trotters boiled overnight with spices. This intriguing combination was the Doodh Na Puff man’s offering, making his rounds early in the winter mornings.

Often consumed by the elderly, they believed it provided strength during Bombay’s chilly winters, a notion we found rather hilarious as children. The arrival of the Doodh Na Puff man was a signal for tea to be prepared. After enjoying the Doodh Na Puff, the remnants, a concentrated sweet elaichi milk, would be mixed with a hot cup of tea, making for a delightful winter morning treat.

This tradition was integral to many Parsi homes during winters, and non-Parsis eagerly anticipated visits to Parsi households to partake in this delicacy. Regrettably, Doodh Na Puff is now a rarity. A few places in Udvada still prepare it during winters. My friend Urvaksh, who once ran Parsi da dhaba at Thalassery, offered it, and it was a hit. But, that too has closed down. This tradition, deeply rooted in my childhood memories of food, heritage, and the audiosphere, seems to have faded away.

Story 3 – What will you eat?

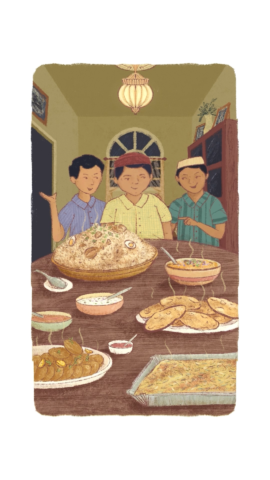

Mumbai in the 70s and 80s was a place where people lived together, dined together, and frequently visited each other’s homes. The sphere of interaction then was vastly different from today. It was a genuinely cosmopolitan city. Growing up in that era, my closest friends were a Bohri Muslim and a Sindhi. The three of us were inseparable. We constantly visited each other’s homes, shared meals, and never once questioned our dietary choices. At my friend Naresh’s house, who was Sindhi, the food was always vegetarian, and we relished it. At Mohammadi’s place, the menu was predominantly meat-based, but there was always a vegetarian dish for Naresh. No one ever forced him to eat meat or ridiculed his food choices.

Whenever they visited my home, my mother’s signature greeting, as my friends often recalled, wasn’t to ask about their well-being but to inquire, “What will you eat?” Declining was not an option. This fostered a profound sense of commensality. When I teach about food, I emphasise that many of today’s problems arise because our food habits have become insular. We’ve restricted ourselves to our communities, mistrusting even our own when it comes to sharing meals. We’ve developed biases, thinking our food is superior to others’. Today’s society is riddled with food fads and misconceptions, a stark contrast to our past.

I vividly remember questioning my mother about why we didn’t prepare Biryani at home after enjoying it at Mohammadi’s place during Eid. Later, I attended a Parsi boarding school where I was introduced to traditional Parsi dishes. However, with a significant number of Surati Gujarati students who were vegetarians, the concept of “your food vs. my food” never arose. We often exchanged dishes. Our staple breakfast was bread and butter, supplied by the renowned Roach Bakery in Panchgani.

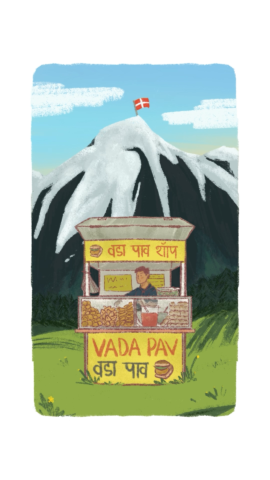

The experiences back then were so different from today. Now, people go on cruises and expect home-cooked meals. They visit places like Mount Titlis and crave Vada Pav. Such expectations would have been unimaginable in my youth. If I had visited Mount Titlis, I would’ve anticipated Swiss cuisine, not Vada Pav. But times have changed, and with more Indians travelling abroad, many are hesitant to try local cuisines. They bring their cooks, their cooking equipment, all rooted in concerns about caste and food purity. While there’s nothing wrong with vegetarianism, the fear that non-vegetarian ingredients might be secretly included is unfounded and divisive. Such fears create rifts and barriers among us. For someone who grew up in the 70s and 80s, this shift is hard to comprehend, as those were times of genuine commensality, openness, and cosmopolitanism.

Story 4 – Topli Nu Paneer

One of the most captivating dishes the Parsis prepare and relish is the “Topli Nu Paneer” or “Topli Na Paneer” in plural. The term “Paneer” typically refers to cottage cheese or farm cheese across West Asia, including Iran, Dhaka, and much of India. Amidst the various versions of paneer, the Parsis have their unique rendition called the “Topli Nu Paneer.” For a long time, both Parsis and Bohri Muslims of Surat held this product in high regard. In fact, Bohri Muslims produced it in large quantities, and Parsis consumed it with equal enthusiasm.

So, what exactly is Topli Nu Paneer? It’s made by taking quality buffalo milk and splitting it using an agent called “Chuzda.” Historically, Parsis, being mindful of their religious affiliations in India, refrained from using calf rennet. Instead, they used “Chuzda,” the inner lining of chicken giblets.

This lining would be finely minced, and a spoonful would be added to a large tub of milk to split it. Nowadays, many home-makers use chemical rennet, imported from England, ensuring the process is entirely vegetarian. Once the milk splits, the curds are collected.

Unlike the typical cheese-making process where curds are heavily drained, for Topli Nu Paneer, the curds are placed in small palm-sized woven baskets. These baskets allow for gentle drainage. The cheese is then flipped to ensure even drainage from both sides, resulting in a light, jelly-like consistency. Once formed, the cheese is placed in mildly salted cold water.

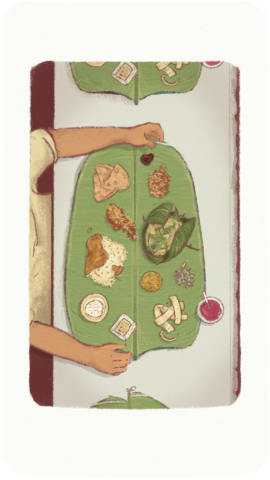

This cheese was a staple in Parsi weddings. It was essential in a Parsi banana leaf wedding meal. The paneer came in various sizes, from standard small ones to larger ones ordered from Surat. They were transported in large milk tubs, packed with ice. The most renowned supplier was Fakir Ji Paneer Wallah from Charni Road, deemed the “Paneer King of Bombay.” Every Parsi caterer had an account with him. He ensured timely deliveries, and many retailers would purchase in bulk from him to sell door-to-door at Parsi households.

Until the late 80s and early 90s, a few vendors continued this tradition in South Bombay. As Parsis migrated to North Bombay, the tradition followed. Today, only one vendor remains in Bombay, and he doesn’t use the traditional baskets. Fakir Ji Paneer Wallah closed his business a while ago.

Currently, the Parsi Topli Nu Paneer is made in limited quantities by young Parsi women trying to revive the tradition. There are a few notable individuals, including my supplier, Delna. However, she produces a maximum of 100 at a time. The golden era of ordering 200 from Fakir Ji Paneer Wallah is now just a memory.

Story 5 – A Life, for a Life

This intriguing story hails from my years working in Rajasthan, conducting archeology in a small village near Balathal in the Vallabh Nagar Tehsil of the Udaipur district. This was in the Mewar region, where we were engrossed in a fascinating site, the subject of my eventual PhD, a multicultural site with a smattering of mediaeval on top, primarily an intriguing early iron age deposit, and a captivating bronze age deposit underneath.

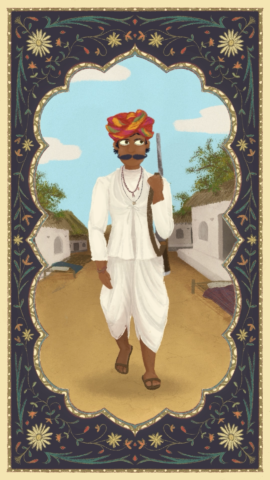

While working there, our local chaukidar was a man named Chatar Singh. Chatar Singh walked around like he had boils in his armpit and like he had done away 2 or 3 people. He was the younger brother of Abhay Singh, the former Sarpanch of the village. Abhay Singh still held considerable influence; the current Sarpanch would do as Abhay Singh advised.

In the first year, Chatar Singh, our watchman, would assemble his bed on a charpai and sleep, his presence symbolising the honour and pride of the Rajputs, protecting the entire site. However, we later realised the villagers were incredibly amiable, and our site didn’t actually require guarding.

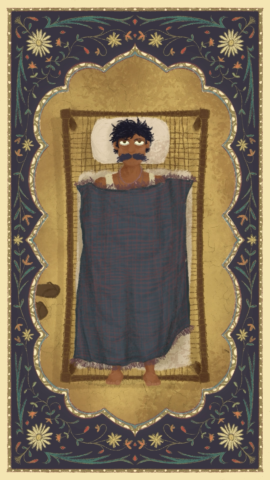

In the second year, we found Chatar Singh unavailable, learning he was gravely ill. The young man, barely in his thirties, had consumed some poor-quality country liquor at a wedding procession and had fallen seriously ill, ultimately being sent home from the hospital in Udaipur to meet his inevitable end.

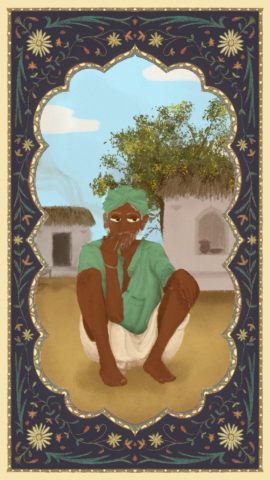

The morning after Chatar Singh was brought home, a decrepit old man, the Bhopa, or the priest of the clan shrine, appeared outside Abhay Singh’s door. This man, a Gamethi tribal, couldn’t enter Abhay Singh’s house due to caste restrictions but held considerable spiritual influence over him. A delicate dance of respect and protocol unfolded, with Abhay Singh and the Bhopa sharing bidis and tea.

The entire village watched as the Bhopa finally revealed that Rada Ji, the clan deity, was extremely displeased with Chatar Singh. To appease Rada Ji, a goat was to be sacrificed. The next day, a solemn, no-nonsense ceremony was conducted, far removed from the cinematic portrayal of Rajputs.

Rada Ji’s shrine was simple, consisting of a wall on the inside of a seasonal dam, adorned with two eyes, a small patch of orange above, a large patch below, and an orange-coloured Trishul, all made in regular vermilion. The goat was offered, and its meat was cooked on the spot by the men and shared among those present.

All the old Bhopa received from this was a bowl of mutton and two bhakris.

The twist in this story came the next morning when Abhay Singh found his younger brother, who was on his deathbed the previous day, trying desperately to wash his face. He was awake and getting better.

A year later, a much quieter, much chastised Abhay Singh and son, offered a goat to Rada Ji, just to say ‘Thank you’.

I remember, after Chatar Singh recovered, I asked one of the labourers working with us, an older gentleman named Ladu Ba, about what had happened. He looked me straight in the eye and said very simply, ‘It’s very simple Sahib, a life, for a life’.

I’m an Archaeologist, Historian and Culinary Anthropologist. I teach Archaeology and its allied disciplines at the INSTUCEN Trust, I write and consult with Live History India and run my own Culinary Anthropology Workshops.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.