After an agonizing three-day journey from Nagaon, Assam, we reached Sukro didi’s house. Didi and her family belong to the Oram or Kurukh tribal community from Sundargarh, Orissa – a state that boasts of the largest number of scheduled tribal communities. The tribes form a part of the Dravidian linguistic community who migrated from the Southern States of India to the Chota Nagpur Plateau.

We were received by an Oram style greeting at the village community hall with flowers, lamp lighting and the women singing songs of welcome. Sukro didi insisted on housing us for the next three weeks.

My stay with Sukro didi’s family introduced me to the Orams’ way of life. At 4 am the village is up, tending to their paddy fields. The women multitask between harvesting, cooking, tending to the household and sending the kids to school. The men take up jobs in the village in addition to farming. Following the religion of Animism or Nature Worshipping, their cooking is a true embodiment of ‘less is more’.

There isn’t any garam masala or yogurt in their curry; there is no coconut milk or curry leaf either. “Bilati, haldi & onion, that’s all we add in any gravy” said Sukro didi. ‘Bilati’ is the pidgin used by the Orams when referring to the tomato, introduced by the Portuguese. The word actually means ‘foreign’ and the fruit is still considered somewhat exotic here.

A comprehensive vocabulary that switches between Kurukh – a Dravidian (southern Indian) language, Sadri and Oria with ripple-less fluidity is one the most interesting and impressive peculiarities of the Oram people. They are adaptive fast learners who know how to make the most of what they have.

“You want to eat Demta? Bhaiya, you are from the city and you are not used to it. It is the poor man’s food!” Sukro didi was shocked. She couldn’t believe that I had done my research and asked for something too personal for them to share. ‘Demta’ is the Sadri (Nagpuri language) word for foraged red ants from the hard wood forest. It is either made into a chutney or a bhaji (stir fry) depending on the ratio of ants to eggs.

I was adamant and took an integral part right from its cleaning till the final bhaji. It tastes like Anda bhurji (scrambled egg) with Sichuan peppercorn, except that the numbness like Sichuan is from the formic acid in the ants. Definitely an acquired taste but oh boy! It was worth it. ‘Demta’ fry also broke through the uneasiness and then came one wonder after another.

Be it ‘Ghungi’ – fresh paddy golden apple snails, picked from rice field, shucked and cooked with bilati; or ‘Khukri’ – wild mushrooms harvested once a year; or freshly plucked Gongura cooked with nigella seeds – the pectin in the roselle leaves turning into a jelly instantly – these were the wonders of this intricate Indian micro-cuisine, that frankly, not many get to experience.

Despite their Dravidian roots, their food doesn’t have many flavours reminiscent of popular southern Indian food. The flavours are clean & the ingredients absolutely seasonal and born out of necessity.

I have been to their paddy fields, harvested rice along with them and realized there is science and economics in everything they do. While back in Mumbai, every steamed rice in a restaurant is most likely Basmati, the Oram tribal eat “Usna Chawal” or parboiled rice which has a higher glycemic index and satiates them for long, reducing their urge to eat frequently, consequently saving their produce.

In a land of plenty, it forms their essential duty to save for everyone and every season. Even in our weekly visits to the haat (market), the frugality was evident. From dried fish and mussels to dry wild foraged flowers that they drink as tea, everything is meant to be stored for the season post-harvest. Despite the limited resources, their hospitality knew no moderation.

A feast of country chicken would never finish without lotas (large glasses) of Handia, a mildly intoxicating fermented rice beer or Mahua, the flower of ecstasy converted into an almost spurious spirit.

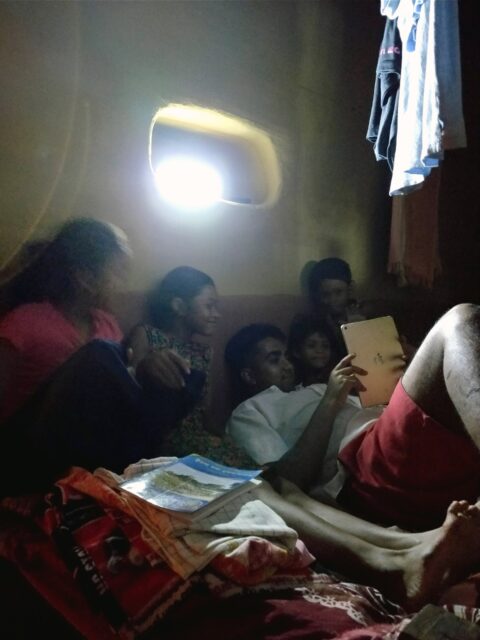

Every night at 7, we would head back to the mud outhouse and sleep peacefully on the khatia (bed) fully aware of the cultural and culinary treasures these people were sharing with us. Next day would bring another exciting adventure and we would get to assist them on their field trip where they would decide what they could pluck and eat.

When it was time for me to head back to the urban drudgery, I couldn’t leave without another of my beloved aunts packing jars of Demta Chutney – which my friends back in Bombay savoured in the form of canapes over cucumber and toasts paired with their favourite glass of Gin and Tonic. It became a raved cocktail starter!

If you are adventurous and want a whiff of their world, travel there with an open mind. Be respectful of their culture and allow yourself to be absorbed by their way of life; and this might be one of the most profound and humbling experiences of your life.

Diganta, or Diggy, is the Growth Partner at The Soul Company, living out of a suitcase and travelling through the many nooks and corners of India (and the subcontinent) in pursuit of meeting great minds & creators- in the field of F&B, Art & Culture. He, through The Soul Company, is building an ecosystem of some of India’s best creators and hence spends a lot of time in meeting interesting people- understanding their culture, cuisine and talent. He was trained to be a chef and has spent time as a Hotelier across India and Sri Lanka, and you will find him either at a good cocktail bar in any part of the country or meeting culinary game changers across the lesser known parts of the country.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.