I spent an hour doing absolutely nothing, transfixed by the magnificence of the Mattupetty lake. “I’ve been here before,” I kept thinking. In fact, I was so sure I had stood exactly at this spot. Except that I had not.

Lush green hills, cleaved by a winding vale.

Voluntarily designed ripples on the calm lake.

A boat or two, strategically placed to enhance the setting.

The sun sneaking behind soft ashen clouds.

Rarely, a herd of elephants, trudging downhill for a drink break at the bank.

I hadn’t been anyplace that resembled this landscape. Yet, I knew this view intimately, like a seasonal childhood memory.

A group of uproarious college kids, walked down towards the lake, interrupting my alleged déjà vu. The stillness of the lake was seasoned with chatter from the small local market, providing some semblance of reality.

Newlyweds and young lovers, rode their powerboats away from families. The striplings stood by the lake posing for their next sensational portrait.

I walked up towards the market, browsing through the azure blue tarpaulin-sheltered stalls selling bric-a-brac. It started to drizzle whilst I was taking a quick glance at some accessories, toys and souvenirs. Hot masala corn, tender coconut water, fresh chocolates from Munnar’s finest chocolate factories, therapeutic oil blends promising dense dark hair – the market was full of bizarre surprises.

The drizzle suddenly escalated to a downpour. I rushed to a slightly roomy stall close by and managed to spot my folks there. They had obviously been beckoned by the chayakkada (tea shop). We huddled together, cold from the gusts of wind and mist.

Image Source: ponnaniperuma

The Western Ghats of Kerala, stretching across Wayanad, Munnar and Idukki, are carpeted in ripe green tea plantations, ornamented with untainted waterfalls. As you ascend towards Munnar, the hills exhale a crisp fragrance, redolent of tea.

The chayakkada isn’t just the little tea shop it outwardly appears to be, it is a zone where the community gathers. And chai is certainly not a mere beverage, but a catalyst that fuels discussions on consequential matters.

Newspaper readings, political discussions, cricket conversations, business deals, college romances – the tea manifests it all.

Image Source: mallu_foodie_bahrain

I’m not a tea zealot but I’ve learnt that the taste of tea, can depend entirely on the setting in which it is discovered. The clouds had descended. We seemed to now be standing in them, heavy rain cascading from the roof.

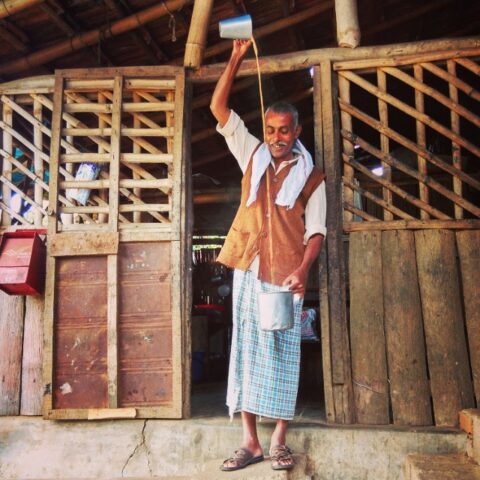

We curled up into our jackets and ordered 5 cups. “Special metre chaya,” the shop helper announced, signalling us to behold the tea master.

The centrepiece of the chayakkada was an antique, barrel- shaped copper samovar. The samovar is a self-boiling hot water dispenser. It has a vertical pipe filled with fired charcoal that heats the water around it, and the teapot placed atop.

Image Source: ab_karma

We moved closer to it, thawing off its heat and gearing up for the theatrical. The tea master measuredly but swiftly crafted a blend of tea concentrate, boiling water, sugar and milk in a big steel pitcher. He then effortlessly and skilfully poured the chai from one pitcher to another pulling them apart, continuing to pour until the distance between both pitchers was exactly one metre.

Image Source: finnykmathew

That was the length of all the tea. Which for an eyeblink was not in either pitcher. It was in the air. He did the metre-long pour several times, acquainting us with its aroma, enhancing its taste, cooling it a little and making it frothy. All imperative to the metre chaya.

The tea master never misses a single drop. That job is for the designated tattletales who come here just to spill the tea.

Next to the samovar, a big cast iron kadhai (wok) was heating oil on the stove. There is no chaya without bajji (pakoda/fritters), and this holds true for all of southern India. The snack chief, plucked out a few bananas from the day’s harvest hanging by a coir rope for the vazhakkai bajji (raw banana fritters). He sliced them thin, dipped the pieces in a batter made of chickpea flour, rice flour and spices including chilli powder, turmeric, salt and native Idukki black pepper.

Mulakku bajji (chilli fritters) and parippu vada (lentil fritters) were also added to the rainy day specials. He quickly batter fried slit banana peppers (for mulakku bajji) and slowly slid the falafel-shaped lentil cakes into the sizzling oil.

Image Source: Dhana Malanthra (munnamidam)

The bajjis were handed to us in a banana leaf layered over a newspaper sheet, served with a spicy red chutney made using grated coconut, shallots, dry red chillies, ginger, garlic and salt; tempered with black mustard and curry leaves.

We stood there, pants rolled up, chai glass in one hand, bajji slathered with chutney in the other, taking in the view.

The chai was a brew of tea dust and loose leaf. A tad bit sweet, owing to its freshness. The bajji was crisp and flaming hot; its heat cutting through the sugared slurps, inducing a quiver of warmth from head to toe.

If you’ve ever travelled along the winding roads that lead to the southern hills of ‘God’s Own Country’ you would know that the visuals of Idukki defeat your imagination.

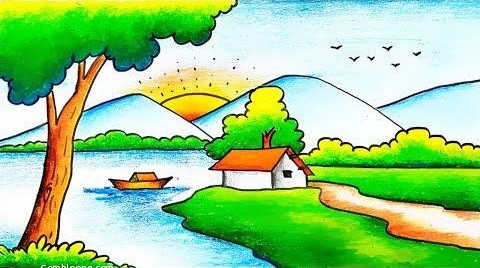

The tea had coaxed me back into my reverie. “Mattupetty looks like a postcard that has come to life,” I uttered. And then it clicked.

Of course. I had seen this landscape one too many times.

Forest green hills. Tall symmetrical trees.

Quiet water, in the valley between.

Replace the tea shop with a lone hut,

And it was the first place my imagination had seen.

I had created this village.

I and many Indian kids, had drawn it over and over in our art files, all through primary school. Our first ever countryside crayon composition. The only drawing inartistic people have ever known. We just didn’t know it was an actual place.

Mattupetty is that drawing.

Only, Mattupetty is better. It has a chayakkada.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.