The streets kept getting narrower as we entered the village. As did the prospects of spotting any factory. The driver dropped us off on the very last street accessible by a four-wheeler.

We started trotting decisively, scanning both sides of the street, looking for a building, without an address. It seemed like a puny village. Only the one unambiguous edifice had to be located.

After a few minutes of pacing up and down several quiet alleys, we reached a lane lined with a few shops and made some ungraceful attempts to ask preoccupied people for directions.

Outside a kirana (grocery) shop, a man was sitting on a parked motorbike, smoking a cigarette, immersed in thought. He waved his hands and probably signalled at us. We walked towards him, his photochromic glasses making it difficult to determine whom he was gesturing to.

Our greetings weren’t entertained. He hopped off the bike, walked briskly, led us to a house and went inside while we waited. We exchanged nervous looks and scanned the area. There was no factory anywhere in sight.

Why hadn’t we hired a guide? Why had we followed an unforthcoming stranger? Should we run back to the car? We found ourselves in a quandary caused by unnecessary spontaneity.

Another man emerged from the house, smiled at us and invited us in. The motorbike man waved at us, then mumbled something and left us with his friend. “Namaskar, factory, factory,” we repeated twice, enunciating clearly to break the language barrier spell.

“Haan, haan, ye factory hai, andar aaiye,” (Yes, yes, this is a factory, come inside) the young man smiled, knowing that we were relieved he speaks Hindi.

This was a proper, peach coloured house. The householder’s two little daughters were running up and down the stairs. The stairs that led to the factory from the veranda. We greeted the house/factory owner and followed our new friend, Nipen.

This must be a regular chore for village inhabitants like the one who had helped us, we realised – to guide aimless, confused researchers, while averting small talk.

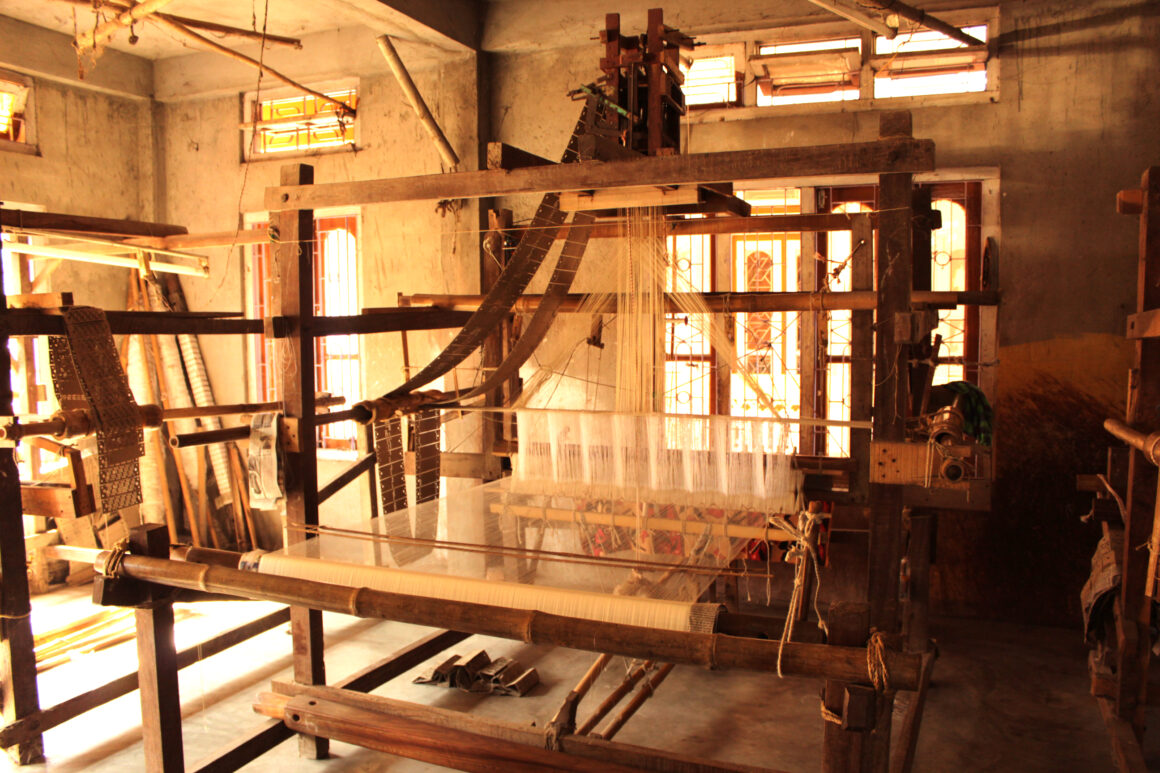

We entered a large room on the first floor. Everyone was at their stations working on their stories. No one looked up as we walked around observing. There was one story of two birds, sitting on a tree, facing each other. Only the storyteller knew what happened next but it seemed romantic. One was historical, seemed like a reinterpretation of an epic, about a glorious royal dynasty. Then another was creating a tale about the forest and its creatures, something possibly wild and mystical. Some were recreating old stories, trying to make it better, each time. There were no writers in this room, these stories belonged to weavers, the sound that seemed like a symphony of rhapsodic typewriters, came from seasoned fly shuttle handlooms and the parchments were yards of fine silk.

About an hour away from the busy Guwahati city, this quiet village was casually weaving wonders, letting the rhythm of looms and etchings on silk tell their tale.

Some weavers paused to greet us and introduced themselves. Dimbeshwar Meghi showed us the pat silk sari he had been working on. Rajan Borah held out a bright red and gold gamosa, fresh off the ‘tatxal’ (colloquial term for the traditional Assamese handloom). Nipen gave us a quick tour while educating us about the various types of silk native to the region.

Sualkuchi houses three varieties of luxurious natural silk. Its signature muga silk might have low permeability, which makes it resistant to dyeing or bleaching but it has an exclusive golden hue and a rare miraculous ability to enhance its lustrous texture with every wash. It is produced by the wild muga worms, found only in Assam, and has hence earned a geographical indication. The tenacity of this yarn is such, that it generally outlasts its wearer.

Pat silk, which is also the most widely used in this factory, is a variety of mulberry silk and has a pearly white colour.

Then Eri silk is thicker and warmer. Primarily used for shawls and throws, this is produced by worms that feed on castor leaves. Eri cocoons are picked up for further processing only once the moth breaks out of the cocoon, unlike with other types of silk where the moth is boiled to procure the fibre. Owing to this differentiator, this fibre came to be known as ahimsa (non-violent) silk and is one of the very few limited edition vegan silks, crafted by nature.

We scribbled intently as artisans from different corners of the room got up to share their wisdom with us. The two girls who had clung onto our bags and followed us, were incessantly giggling at our questions, wondering why we had come this far to take some notes.

Another gentleman, Maniram Das, excitedly invited us to his workstation to show us what he had been working on. He signalled at us to pay attention as he couldn’t hear our questions or give us any answers. So we watched and learned.

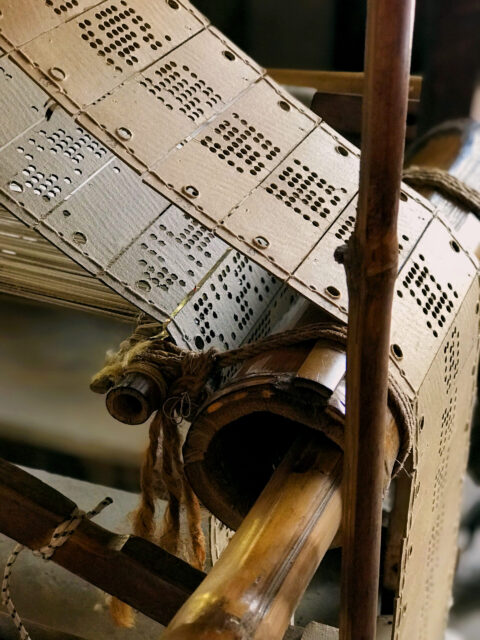

He demonstrated how the fundamental purpose of the loom is to maintain stiffness and tension in the warp threads. The weft threads are then interwoven horizontally, through a chain of punched cards, which direct the designs onto the loom.

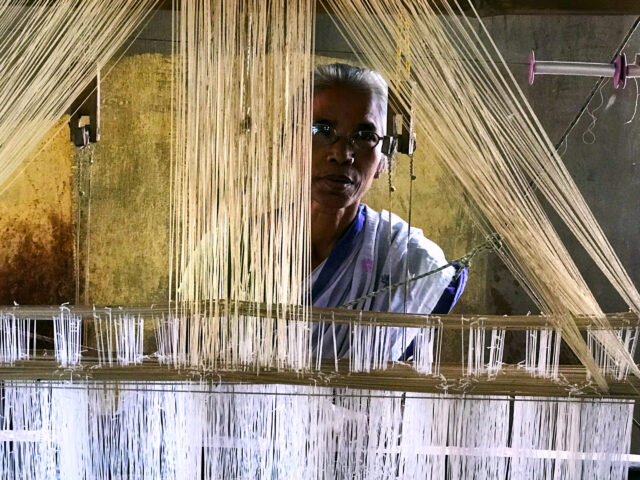

On one corner of the room, a senior craftswoman was weaving a gold and white fabric. She was engrossed in her meticulous design and did not look up as we approached her station.

“Inka naam kya hai?” (what is her name?) we asked Nipen. “Meena Burman,” she looked up from the loom and said, then went back to it in a second, unperturbed by our prying.

One look around the factory made us realise – for those passionate about luxurious clothing and haute couture, this is the place to visit. No two creations are identical. There are cards to guide the designs but the weaver is the ultimate artist. The little imperfections that come from an artisan’s hands each time, are unique to just one wearer. What a privilege it would be to own a Meena Burman exclusive!

We thanked Nipen for the weavers’ masterclass and left the house factory. On our way back to the car, we learnt that the numerous bamboo structures lined alongside the streets were in fact, silk factories. A group of women had just finished their tea and were getting back to their looms as we entered one shack.

There were also some with power looms, but the handweavers clearly hold a special stature in Sualkuchi. This we gathered from the many marketing geniuses at the storefronts who would first show the customer some machine woven mekhela sadors (traditional Assamese two-piece sari) and then reveal the handwoven ‘original’ as the most magnificent exclusive for those with fine taste.

We also learned that every house around us was involved in the process of silk making. Two women smiled at us as we were walking past their house, and insisted that we come in. All the furniture in the house was pushed to the walls and the centrepiece was a small wooden machine used to make silk yarn from fibre. Manjula Kunjo ji and her daughter-in-law promoted their treasured instrument with pride. We stopped by their house for all of five minutes and we couldn’t understand each other’s words; but they offered us some snacks and water, shared their craft with us and hugged us when it was time to leave.

Somewhere along the northern banks of the Brahmaputra river, a village full of anonymous designers were creating the most beautiful fabrics, drawing inspiration from history, nature and tradition. They were immersed in scrolls of silk, painstakingly handcrafting intimate stories. While each story might have been open to interpretation, only the designer knew how it unfolded, if it was humorous or melancholic, and what the end was, if it ended at all.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.

Very good work

Thank you!