Kamla, Anita, Manju, Lalita, Deepa.

Little white stickers with names handwritten in biro were stuck on berets, socks, sweaters, gloves, mufflers, dolls.

Baskets and racks were piled with fresh-off-the-needle designer knits in yellows, greens, reds, blues and everything in between. The front portion of the Kilmora shop was the woollen knits section.

The rear half was an assemblage of colour-blocked lustrous weaves. Shawls, stoles, coats and jackets, also with handwritten labels. The fallible perfection of a handicraftsman personified every fabric. I stood there, imagining myself falling into this utterly saturated vortex of yardage but quickly snapping out so as to not upset the merchandising at all.

Sargakhet village – where the Kilmora Handicrafts and Local produce store is located amongst a few other shops– is a couple kilometres from Mukteshwar (Kumaon, Uttarakhand); a short storybook walk along the hilly woods. The plum, apricot and apple trees bringing out the thrilled fruit thief in you, but in a passably childlike poetic way. Unless someone sees you, then you’re just a piddling, puny pilferer.

Anyway, once you are inside the shop, be wary. Your vanity will get the better of you. You will be ensorcelled by the too-muchness of colour. And your small voice will have its way.

“You’re not going to avoid the Pulchritudinous Purple shawl that you can wear to work or parties or work from home parties when you’re feeling fancy. Are you?”

“Are you going to ignore the Narangi (Orange) and Fandango Pink dushala, just because it is on the bottom left of the shelf? Go on! Drape it, prance around and imagine how it would look with your Buttery-Ivory kanakambaram gadwal saree or that Custard Yellow damask sherwani at a sunlit winter wedding.”

“Look! Look at that collarless Crimson coat. Must you live a life of regret without it?”

“Hey! Don’t forget to pick up the Pansy Purple beanie on your way out.”

We spent almost 3 hours in the shop, all of a doodah about what to buy and what to part with (with a heavy heart).

Kilmora’s products are not particularly thrifty. We applied all our textile knowledge to assess if these were hard-wearing pieces. One frequenter popped his head in to say ‘hi’ to Mr. Dharmanand. They exchanged a can of timeworn laughter which ended abruptly. Then he delivered a short monologue about his favourite, most durable, Cocoa Brown shawl he had bought from the store 7 years ago. 7 years. I clutched my Pulchritudinous Purple shawl to-be tightly.

Who had visualized these pieces? Someone who deeply understood design and was breaking fresh ground by experimenting with colours and patterns.

Mr. Dharmanand, the store manager, mentioned the name of one ‘Jeena ji’ and offered to help us meet him.

Next morning, after a short hilly drive we reached the production centre in Kasiyalekh village. We got out the car and followed one of the staff members up a steep path cutting uphill.

A petite, lean man, dressed in a shirt, trousers and slippers; chandan-tilak (sandalwood and vermillion) on his forehead – hailing from a neighbouring village – was waiting for us.

We exchanged hurried opening pleasantries and followed him into a small room, a yarn library of sorts. Spools of colourful, very poppins-like natural yarn were neatly arranged on metal shelves. In one corner, was a small workstation with a desktop computer. “Ye office hai. Yahan designs bante hain, fir upar weaving ke liye jaate hain.” (“This is the office. The designs are made here and then sent upstairs for weaving.”)

Upstairs in the warping and weaving rooms, we saw this common man’s brilliant imagination come to life. An orchestra of fly-shuttle handlooms, managed by nimble-fingered, twinkle-toed weavers was performing one of the most chromatic productions I’d ever seen. Every combination was one you didn’t know you were looking for.

Rajendra Singh Jeena is a designer of the first water; and his curiosity constantly pushes him to produce perennial styles worth investing in.

His grey matter is jam-packed with colour; that’s his gift. He knows which one should lead, which should follow. Which of it to put more and which of it to only drizzle. He knows where intricacies would make sense and where colour-blocking would work better. It’s just all there in his head, waiting to be woven. But he cannot tell you how his mind works. He doesn’t know. He does what he feels like and mostly, it works.

We spent a while on the terrace talking about Kilmora’s efforts towards giving back to the community by reinvesting its earnings in rural employment initiatives and improving product quality.

Ravindra Singh, an exceptional craftsman – and weaving unit supervisor – who was patiently answering all our pesky questions, shared an interesting detail. That while their shawls are soft and wonderfully warm, they’re not wafer-thin because, of course, they’re painstakingly hand-ironed.

They spoke of all their plans and creative experiments with wholesome excitement and we were hung on every word.

We stood there, beholding the hill forests and tiny villages as far as the eyes could see. Jeena ji appeared pensive for a few seconds; staring at the many trees laden with fruits and berries, probably thinking of his next drafting plan…

As for Kamla, Anita, Manju, Lalita, Deepa.

We learned a little bit about the Kilmora knitting sisterhood.

Once a week, the knitting sisterhood gathers from nearby villages to work together and knit stories into whatever goes onto the shelves next.

Sometimes, a bringer of glad tidings knits a bright pink beret. Sometimes, a forlorn knitter siphons sorrows into understanding, warm Boysenberry mufflers that will keep you snug on a bone-chilling day.

Once, a sister was telling the story of how she singlehandedly sent her children to school and the sisterhood was so proud of her. I like to imagine, she knit this story into the warmest pair of Ruddy Blue socks that I’ve now worn to the snowy peaks of khardung-la.

Remember the Pansy Purple beanie? I am certain it is the outcome of a rather paradoxical family drama, full of twists and turns. I also wore that and stomped in the snow; woolly headed because of the minus 17 degrees but pleased to be snuggled in the beanie and someone’s story. All of it giving me the heebie-jeebies.

Some of the stories might have been irksome. That day maybe a dull colour was used, but all the forehead furrows and abuses hurled became knotty patterns on the monkey cap which now smothers someone else’s head.

Is that not why we must know who makes our clothes? Much like how we like to know who makes our food. Send compliments to the artist who suffered an attack of croochie-proochles because they wanted to finish the story that day?

Source : instagram.com/kilmora_kgu

Kamla was the first supervisor of the Kilmora knitting sisterhood. She’s a stickler for perfection and approves only the finest of knits and trains other knitters to strive for perfection in their work.

Source : instagram.com/kilmora_kgu

Anita, also a knitting supervisor, shuffles between different knitting groups and trains the knitting groups in new designs.

Source : instagram.com/kilmora_kgu

Manju, I’m told, is one of the knitting assistants, who juggles between farming and knitting gorgeous pieces for Kilmora.

Source : instagram.com/kilmora_kgu

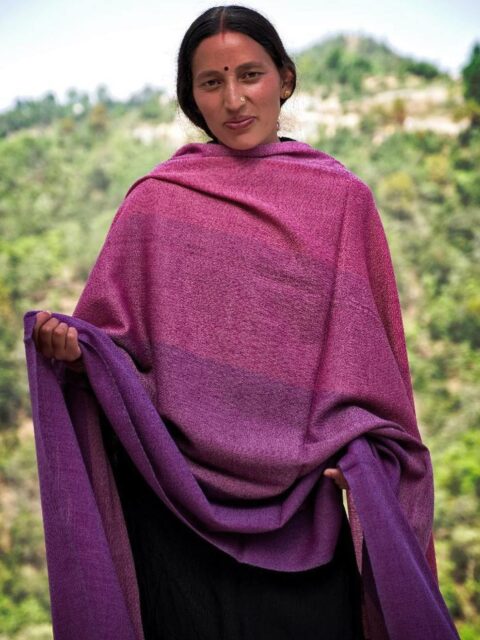

Lalita, another beautiful knitter, sometimes graces Kilmora’s Instagram feed, as a shawl model.

Source : instagram.com/kilmora_kgu

And, Deepa, whose knitted dolls may or may not have stories but now sit beside the many dreamy little children whose fantasies they have become a part of. I hear one doll, known as Po, is attending online classes and accompanying its small human on The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane these days.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.