It’s hard to put your faith in sustainable and healthy food practices when the options offered to you aren’t as appealing, if not better. After all, it is the era of food enthusiasts, scouring through narrow lanes, in search of the best food, instigating competition amongst restaurants and questioning their existence.

It was quarter past 2 and most eateries in Chennai shut at 3, then open for dinner at 7. I decided to head towards Adyar and make a quick decision en route.

Since the weather wasn’t feeling particularly jaunty, an aircon would be a determinant. My stomach was growling and I’m not very likeable when I’m perspiring, hungry and anxious, so something delicious (unhealthy) would be antidotal. Better if I could find someplace new. It would seem I wasn’t at my decisive best because by the time I applied these filters, I had reached my provisional destination.

It was a main road, lined with jewellery shops, no tree around to save my head from latent combustion. No restaurants. I walked along the shops, my nape burning in the heat. At 2:45 pm, I was on the brink of dropping this plan and sliding into one of the shops for five minutes of crisp 23 degrees, when what appeared to be a bright orange house, inside an adjacent gully caught my attention. I squinted and strained trying to read the signboard hung to its side. I could decipher only the last word – Bhojanam (Meal).

I walked closer, my curiosity building towards this residence that was probably a restaurant. And it was. Bereft of choices, I grudgingly darted up the stairs of Prems Graama Bhojanam (Prems Village Meal).

A lanky steward received me with a bizarre greeting, “single aa?”- the accepted way across rustic southern Indian eateries to enquire if you’re an unaccompanied diner.

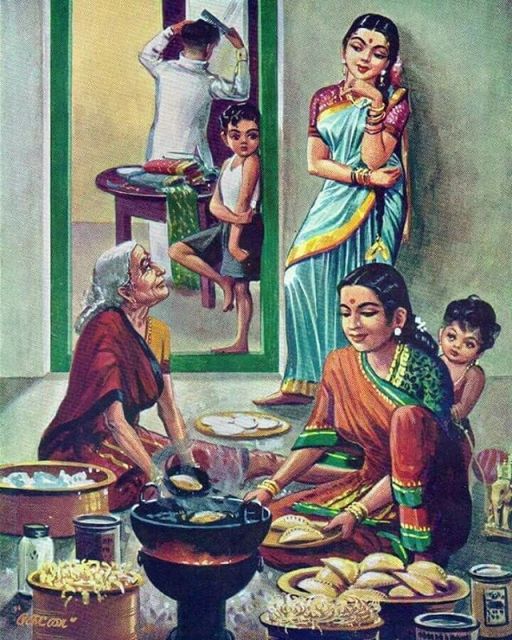

I nodded but shot him a look that conveyed that I was offended by his acknowledgement of my solitary visit. He sincerely took no notice and gestured me to come along. I stepped in and realized that this was in fact, a house, converted into a modest restaurant of sorts. The walls were bright orange and green in colour with murals painted on them.

My server pointed towards the spot he had selected for me, which was a wooden bench-table meant for one person. I smiled, relieved that many people came here to eat alone; that his question wasn’t a judgement.

The interiors were unboastful but expressive, with utilitarian seating and conspicuously dressed walls. Being a village-style mess, it was devoid of air conditioning, but had a pleasant ambience with ample windows and wall fans. I mentally unchecked the filters I had applied.

The ‘mess’ format was originally that of a dining hall, purposed to facilitate social interactions amongst the militia. Scaled-down adaptations of this concept eventually sprouted across many cities in Southern India with the booming bachelor population, migrating in search for better jobs. In Chennai (then Madras) – and several other southern cities and towns – the mess has endured the erratic market dynamics and the whirlwind of disruptions caused by new-fangled establishments. To this day, it caters to the homesick lone eater, providing nourishing meals that are benevolent to the pocket.

Although it was afternoon closing time, they could either see how hungry I was or were generally kind enough to take my order. Indecisive about picking from the menu and ambitious to try many dishes, I concluded that the mini meal thali (platter) would be ideal.

A compartmentalised steel thali lined with an enthusiastically green banana leaf arrived soon. It had 4 varieties of rice, kovakkai (kundru/little gourd) sabzi (sautéed vegetable) and peanut chutney. These southern staples ought to be spicy, oily, rice-y, I presumed.

I ate every last grain and speck of the not-so-mini thali. There was a small steel pot of water on my table which I decided not to drink. I was thinking of checking what’s available for dessert when the server came to inform me that I would have to pay cash. I had none. I rummaged through my wallet and found 100 rupees, so I dropped the dessert idea (as if not ordering dessert meant I could pay the bill). My bill was all of 97 rupees. I was about to squeal in disbelief when a young woman came to my table and asked me to try some dessert. I pretended I was stuffed. A small bowl of their sakkarai pongal (jaggery and rice pudding) was brought in and she said, “please try some, it’s on us.” I dropped the act and gobbled it up.

I acknowledged that I was feeling surprisingly light after all that rice. “Hah, that’s not rice,” she chuckled. I felt tricked. She poured a glass of the water I had mentally labelled as unfit for consumption and pushed it towards me. I took a sip to realize that they had put some thought into the water too. It was infused with tulsi (holy basil), edible camphor, cloves and cardamom – formulated to help improve blood circulation and regulate blood pressure. She then brought the menu and sat down to tell me the story of Prems Graama Bhojanam.

Mr. Krishnamoorthi, the owner of the restaurant, is this young woman’s father. In the long span of his career, he has travelled to many villages often eating at the homes of locals. He always dreamt of setting up a restaurant someday and he drew his inspiration from these travels.

Prems is a concept vegetarian eatery styled like a village mess that stands true to its promise of quality, taste, affordability and health. Had I not been in a hurry and had browsed the menu even a little heedfully, I would have known I was about to eat healthy. I’m glad I did not.

As kids, when we were fussy eaters, our mums always found a way to mask the less-liked foods and con us into relishing them. That’s precisely what my experience at Prem’s was like.

The coriander ‘rice’ was a herbaceous dome of kodo millets; fragrant and temperate, with crispy interruptions from roasted peanuts.

The sambar sadam (rice) was generously tempered with dry red chillies, curry leaves, mustard seeds; perhaps some pepper. The flavour was piquant from tamarind with sweet implications from carrots, shallots and a dash of jaggery. The sadam was of course, foxtail millet, not rice.

Prepared with the barnyard millet, the rasam sadam was fiercely peppered. Further intensified with curry leaves, dry red chillies and mustard seeds, this tomato based broth-curry had a sharp, sense-stirring character.

The calm after a storm was thayir sadam or curd rice – the little millet version. Mildly tempered with some curry leaves, mustard seeds and roasted dal, this was the customary palette neutraliser preceding dessert.

The peanut chutney adequately performed the role that is generally expected from a pickle – of the bold supplement, should you wish to add some zing to your meal.

Typically, vegetarian meals in many southern households must have one variety of vegetable, which is either a boiled then sautéed preparation or a crispy, fried version to accompany any dal/curry-rice. The little gourd sabzi was definitely not fried, but lent the perfect bite to the curries and made the meal wholesome.

Made with black rice and jaggery, the pongal was sublime, like a traditional temple prasadam (holy sweet) with a pleasantly sweet taste. It was everything a last course should be – a gratifying conclusion to the mindful millet story.

A story dedicated to honouring the diversity and multipotentiality of one cereal grain. Mr. Krishnamoorthi’s recipes and continuous experiments are representative of the endless possibilities of these small-seeded grasses.

Image Source: Prems Graama Bhojanam

The menu at Prems celebrates the remarkable range of textures, flavours and nutrition that can be achieved with millets alone. From puffy, grainy rice to creamy pongal and halwa; soft porous idlis to thin, crispy dosas – this grain is a high performer.

Image Source: Prems Graama Bhojanam

It can be sweetened or spiced, curried or dried, and is a rich source of vital nutrients like manganese, magnesium, copper and phosphorus. It is a rain-fed crop that doesn’t demand excessive water and can grow successfully without pesticides and fertilizers – thus reducing its environmental footprint to a miniscule of that for grains like wheat and paddy.

This raises a legitimate question. Why hasn’t a grain so economical, easy to cultivate in arid regions, far healthier than the carb-heavy white rice, equally capable when it comes to taste and variety, ever been considered a staple in the Indian household?

Majoritarian cultural habits, and an agricultural shift to high-yielding crop varieties like rice and wheat during the green revolution, overshadowed the capabilities of millets. With time, changing these farming systems and eating habits became challenging.

The era of thematic restaurants began and words like ‘sustainable’, ‘organic’ and ‘farm-to-table’ became highbrow concepts meant for affluent diners. It didn’t matter which farm the food came from and that it wasn’t revolutionising any mainstream tables. Consequently, it didn’t matter if the grain itself was sustainable. All ‘native’ food innovations were still confined to the comfort zone of rice and wheat. But it was a start.

With establishments like Prems, the knowledge of traditional Indian grains and vegetables has been made accessible to the masses, sans the frills.

The Krishnamoorthi household has revisited indigenous agricultural practices, painstakingly designed recipes and then developed economical and delicious dishes to drive their point home. If you visit them, they will earnestly share their knowledge with you, because for them, this isn’t just a concept – it is a way of life they’re attempting to encourage.

Was the food at Prems glamorous? Was it plated for the camera? Was it accompanied by persuading descriptions on the menu? Was it cooked with the objective of sending you into a food comatose? Quite the contrary.

It was unembellished. It was what simple food looks like. It wasn’t endorsed using provocative descriptions to convince you – in fact it had no descriptions at all. And it most definitely wouldn’t send you into a lull. It might, however, leave your gut feeling light, and your mind feeling clear.

When it comes to conscious cooking, there is a lot that can be attributed to Prems Graama Bhojanam. It has stayed true to its identity of a humble village mess. It has pushed for millets as a custom not a fad and has steadily influenced consumption tendencies over the years. Why don’t we see it hyperbolized on the influencer market, by our quinoa craving comrades? Maybe because it decided to be approachable, not aspirational. Maybe because we’re not instagramming enough.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.

Love it!

Thank you, Rini. Glad you enjoyed the read.