If you were to seek out what comfort food looks like in Sindhi cuisine, you probably would not stumble upon singar ji bhaji. This unassuming dish—made with tomatoes and singar, known as sev in Hindi—is not on most blogs or listicles covering the ‘Top 10 Sindhi Dishes You Must Try.’

My contention with these listicles goes well beyond their surface-level approach to popular Sindhi dishes, which is a problem that almost all cuisines face in mainstream media coverage. What really irks me is that they fail to include dishes prepared on the day-to-day, and singar ji bhaji is one of them. Upon a cursory glance, singar ji bhaji may seem like a post-partition adaptation of the Gujarati sev tomato nu shaak, the Rajasthani sev tamatar sabzi or the Maharashtrian shev chi bhaji, when in fact singar ji bhaji is emblematic of Sindh’s rich regional cuisine in its own right.

My father grew up in a household where Sindhi food was the primary cuisine, with the rare dose of Maharashtrian food when they wanted to enjoy masale bhaat and pooranpoli. His Pune upbringing dictates that his Marathi must be as good as his Sindhi, and that he knows where to get his favourite misal and Maharashtrian thali in the city. But despite the acclimatisation to his home of over fifty years, his heart belongs to the quick and easy Sindhi meals he was raised on. Living in a joint family meant that dishes had to be simple, filling and resource friendly. A dish that therefore dominated my father’s childhood meals, and one he holds close to his heart to this day, is singar ji bhaji. The warm tomato mixture cooked in onion with a sprinkling of chilli, coriander and turmeric powder and a generous addition of thick, crunchy singar alongside fresh chapati is his ultimate joy.

I’m aware that using sev in a savoury dish is very common in multiple states across India, but the point of this article is not to figure out who came up with it first. The point instead is to stake a claim for the Sindhi singar ji bhaji being an iteration in its own right. From the etymology of singar and its introduction into various Sindhi households, both before and after Partition, to how it appears on the plate as singar ji bhaji, it is quintessentially Sindhi.

In the context of snacking, singar usually refers to any type of sev that is thick and crunchy., However, singar is also used in a Sindhi dessert that is decadent, soft and instantly melts in your mouth—Singar ji mithai. It involves combining unsalted, thin sev with unsweetened khoya or mawa which is then infused with blitzed up cardamom, rosewater essence and saffron, and finally topped off with slivered almonds and pistachios. Where singar ji bhaji and snacking mixes use thicker singar, singar ji mithai in the last few decades has been prepared with thinner singar. The word singar is only now used to refer to all and any kind of sev, but before the Partition, it was murmula.

“It’s a question of which part of Sindh someone is from,” says Sapna Ajwani, London-based Sindhi supper club host and author of Sindh: Sindhi Recipes and Stories From a Forgotten Homeland. “Lower and Central Sindh have less of a Lahanda or Balochi influence hence the language has retained older vocabulary.”

Murmula was a besan preparation that was used like sweet boondi—often found in the form of a laddoo—that was added as a topping onto Sindhi kadhi. In fact, it was also murmula that was used in singer ji mithai, but its meaning changed over time as singar became more widely used. “Even the singar used in singar mithai is long and thick and not thin like nylon sev which has become more prevalent. That is a Mumbai bhel influence,” Ajwani adds. What used to be murmula became singar and what used to be thicker singar became influenced by the street food culture of Mumbai, a city that houses many Sindhi families.

This begs an important question: did cooking with singar, especially as a savoury dish, start before or after Partition?

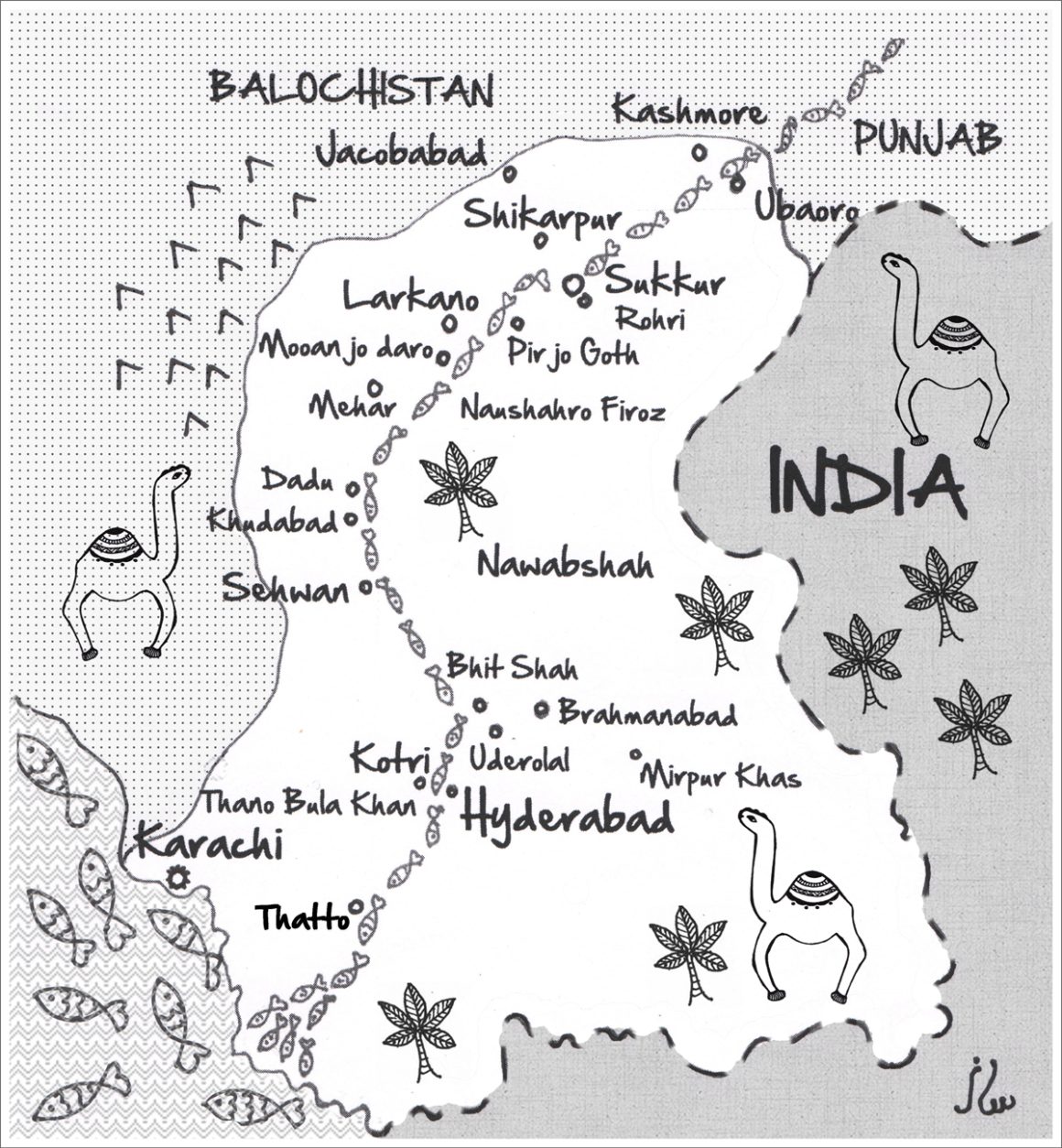

To answer this question, it’s important to understand the geography of Sindh (here, using this beautifully illustrated map created by and taken from Saaz Agarwal’s book on Sindhi culture, Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland). The Easternmost region of Sindh, Tharparkar, borders parts of Rajasthan and gets its name from the Thar desert that stretches beyond borders and British official Stuart Charles Parker that contributed to the development of this region under British rule.1 Sindh in its entirety is a very dry, arid region, and even before Partition, the British undertook lots of irrigation and canal construction projects to provide water for agriculture to parts of the region that received very little rainfall.2 Tharparkar is one such region where the desert conditions made it difficult to have a consistent supply of fresh produce. Perhaps it was due to these geographical constraints that the people of this region found besan to be a lucrative alternative to make dishes more filling – just like Rajasthani cuisine. From using it to make singar and adding it to the curry our community is eponymous for, to dharan ji kadhi where besan tikkis are fried and cooked in a tomato and onion gravy, there’s no doubt that besan and its preparations hold an important place in a Sindhi kitchen.

While researching this piece, I received many responses from some members of the Sindhi community saying that singar ji bhaji was a dish they loved eating while growing up, much like my father, and that they too came from households that almost exclusively cooked Sindhi food. Assuming that this generation grew up in the 70s and early 80s, this was not a time when television programs shared a wide array of cooking shows covering different Indian cuisines. Nor was it a time when social media and regional cuisine content creators existed. It is possible then that that generation of Sindhi cooks were preparing recipes that had been passed down to them or shared only within the Sindhi community. While Sindhi cuisine does boast several dishes using besan, there’s no way of being sure that they’re all post-partition adaptations of Rajasthani cuisine, as they’ve existed well before the Partition generation moved to India. Singar and its myriad of uses, then, have possibly also been handed down to generation after generation well before Partition even became a reality.

S. Chhabria, 95, born in Shikarpur, Sindh, recalls singar being used well before Partition, sharing how singar ji kadhi used to be one of her favourite dishes to eat. She says that the singar we use now to make savoury dishes is the gathiya sev influenced by Gujarati cuisine, and that singar was somewhere in between too thick and too thin back in the day. Where singar was something she actively grew up eating even in Shikarpur, it is still not the case that every Sindhi family prepared or consumed singar this way. “My aunt tells me that when they migrated to Jodhpur, they saw the Rajasthanis eating gyantha, the thick sev that comes with bikaneri bhujia in a yoghurt kadhi base with no onions or garlic. They started cooking it at home inspired by a local recipe of their host state. No singar or sev was ever used,” says Ajwani.

That’s the thing about cuisines—they defy any attempt at standardisation. Even when talking about Sindhi kadhi, no one family will use the same vegetables, even more so after Sindhis migrated to India and adapted to local produce. While singar ji bhaji may not be a cherished childhood meal for Sindhis across the board, it was still something that was actively cooked in certain Sindhi homes before and after Partition. Even if the recipes were adapted to geography, these modified singar dishes were still cooked in the traditional seyal way—wherein chopped tomatoes are cooked until soft in a mix of browning onions, and on occasion even garlic, and then combined with chilli and turmeric powder—to add some Sindhi touch to it. Seyal is the blank canvas for almost all Sindhi culinary creations, and you can cook bread, leftover chapati, veggies and even meat this way. While the ingredients for seyal will differ from family to family, what it contributes to a dish is a deeply savoury and tart backdrop of flavour—not unlike an Italian pomodoro sauce.

I always used to associate the inception of singar ji bhaji with times of scarce resources, or the lack of fresh vegetables. While that is true to some extent (there are simpler versions of this dish where singar is cooked in only water and jeera), it is not necessarily viewed as a reflection of hard times by the people who love eating it. It is important to acknowledge the prevailing socio-economic circumstances of this dish, but I don’t think that’s what singar ji bhaji should be all about. I also don’t think that singar ji bhaji is supposed to be a dish that is emblematic of the struggle, the dispersal and the disjointed nature of the Sindhi community, and that eating it will magically incite pride in our heritage and lineage.

What I do think singar ji bhaji provides is an opportunity to look at history, regionality and the memories of the Sindhi community, and to realise that our cuisine is so much more than what it is portrayed as in mainstream media. We’re just known for Sindhi kadhi, dal pakwan, koki and saee bhaji, while the food that we actually have grown up eating for generations remains overlooked in some passive attempt at representation. Furthermore, our cuisine is seen as some melting pot of influences from neighbouring states on both sides of the border, but it is so much more than the sum of its parts. Sindhi cuisine has an identity of its own. Singar ji bhaji goes beyond being thought of as an imitation. I’m sure that there exist many other such recipes in Sindhi cuisine that give people comfort, solace, and nourishment, and allow them to feel like they’re part of something bigger than themselves. I hope in due course that those recipes will unearth themselves and not be lost in translation. For the time being though, a ladle-full of singar ji bhaji and some warm rice would hit the spot.

1Aggarwal, S, ‘Sindh: Stories from a Vanished Homeland’, 2012, pp. 80

2Ambekar, G. R, ‘Crops of Sind: Their Geography and Statistics’, 1928

Singar ji Bhaji

Ingredients

(Serves 2)

- Oil: 1 tbsp

- onion: 1 chopped

- Tomatoes: 2 (chopped or pureed)

- Grated ginger: ½ tsp

- Chilli powder: ½ tsp

- Turmeric powder: ½ tsp

- Coriander powder: ½ tsp

- Water: 1 cup

- Garam masala: A pinch

- Singar (I like to use Ratlami Sev): ½ cup

- Salt: to taste

- Chopped coriander as garnish, optional

Method:

- Add oil to a pan on medium heat and add chopped onions.

- Once the onion browns, add pureed or chopped tomatoes, grated ginger and chilli, turmeric and coriander powder. Traditionally, tomatoes are pureed for this dish but I love the mouthfeel of chopped tomatoes.

- Let the mixture cook and once the oil begins to separate from the tomato mixture and the tomatoes don’t smell or taste raw, add a cup of water and bring it to a boil.

- Once the mixture boils, turn off the gas and salt to taste and a pinch of garam masala.

- Add singar of your choice just before serving so it doesn’t become limp and lose shape. Stir it around a bit so the singar absorbs the seyal flavours of the tomato and onion.

- Add chopped coriander as an optional garnish and serve with hot rice or chapati.

Harshita is the Marketing Lead at The Locavore with a background in book publishing and sustainable food systems campaigns. She’s also a food writer with a newsletter called Sindhi with a Dash of Hindi wherein she looks at Sindhi foodways through the lens of history, gender, and migration. In her spare time, she watches compilations of BTS, cats, and K-dramas, preferably all at once.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.