The elderly have no regard for calculated talk. They’ve understood the futility of filtered lives and hence prefer to just cut to the chase.

When she first answered my phone call, Zaibun Nissa was in no mood to speak. I had just started talking when she impatiently asserted “Aap mujhe agle hafte phone kariye, abhi mai bohot busy hun,” (call me next week, I’m very busy at the moment). I agreed to call her the following week and emphasized how much I wished to meet her.

She sounded worried but I did not want to intrude so I said thank you and was about to disconnect the call when she suddenly started talking. I spent the next few minutes learning about her family and attentively listening to some unpretentious heart pour, her tone altering from an aggressive grumble to a neighbourly apologetic one.

Her candidness felt strange but inspiring. It made me realise that the old adage, ‘with age comes wisdom’ actually meant, ‘shedding all pretence in the interest of time’. I promised to offer my dua (prayer) for her ailing nawasi (granddaughter) and disconnected the call.

I called her back exactly a week later to learn that my dua seemed to have worked. And although we had spoken just once on a temperamentally challenging day, an abridged familiarity had been established between us.

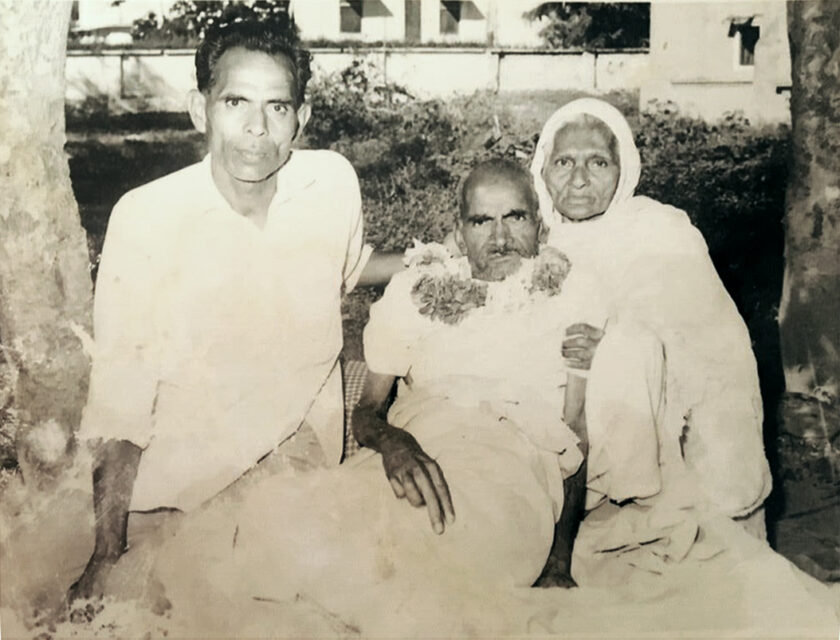

This time, she spoke of her father. Her voice was heavy with reverence and emotion. She would often say, ‘mai toh cook hun, mere father kaafi unche kaarigar the,’ (I’m a cook but my father was a very superior craftsman). I could hear her voice breaking whenever she remembered him.

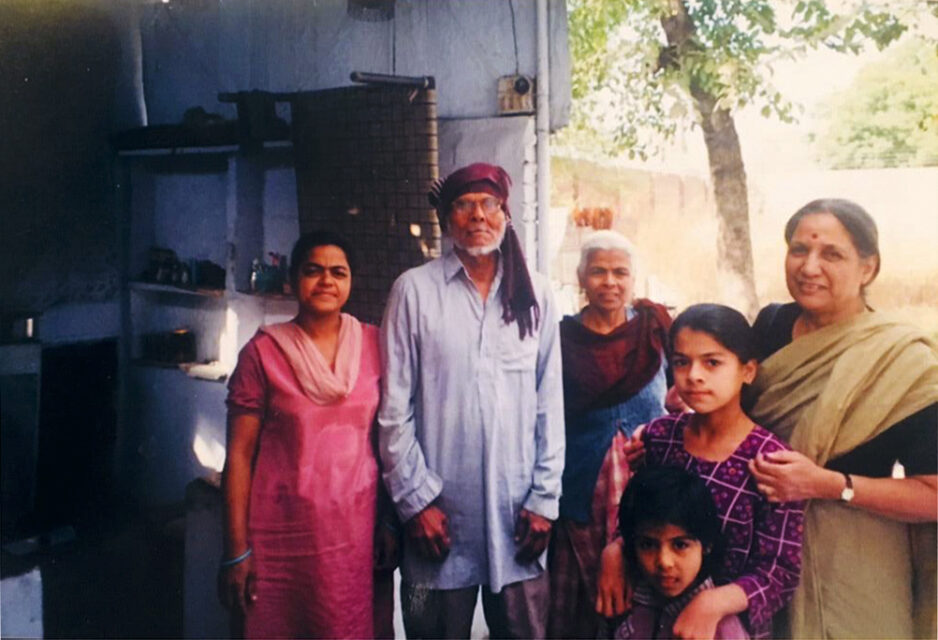

On the day we arrived in Jaipur, we went straight to see her. Sitting around the corner of the C-scheme masjid gate, she smiled, leaning onto her cane as she stood up. We stepped inside the gate into a small veranda where a cot and some chairs were arranged for us. We sat down to talk as the sound of the afternoon azan (prayer) filled the masjid (mosque) premises.

The veranda, where Zaibun Nissa meets all her visitors, extends from her 50-year-old residence and kitchen. The cabin has an enclosed rear portion, horizontally divided into two half floors with a small iron step ladder connecting the two. In the upper half, are her cooking appliances, cauldrons and treasured masalas, the lower half is her personal space – both accessed by little bright blue doors. The front of the cabin has two small refrigerators, an angeethi (a traditional braizer) and a sundry of kitchen things.

When Zaibun Nissa took charge from Ahmed Ali, the regulations were challenging. Her father dissuaded her from leaving the house: “ye meat daaru ka kaam hai” (this work involves meat eaters and alcohol drinkers). So, the condition for Ahmed Ali’s customers and for Zaibun Nissa was that she would only operate from the confines of this house, and keep out of the royal rasois (kitchens). Whoever wanted the food could pick it up from her home-kitchen – and that’s how it’s been since. Not having access to formal education, being born at the unsettling time of partition and being estranged by her husband could not deter Zaibun Nissa from becoming a successful entrepreneur. She found a way to thrive within the realm of patriarchal demarcations and through longstanding disagreement with the masjid authorities over her ancestral property in the compound.

While she often recalls how she had no choice but to learn this skill to earn a living, her resolve to eternalize Ahmed Ali’s legacy tells another story.

On our second call, a week before we met, when I mentioned that we would love to taste her food, before saying anything she instructed that I place the order well in advance as she’d have to order the meat in time for it to be fresh and cut precisely. Thereafter, every day, she would call and remind me to bring a canister for takeaway.

The rules at Zaibun Nissa’s are straightforward. It is a slow kitchen, and it’s a home kitchen, not a restaurant. She does not entertain orders on short notice so give her at least 24 hours of prep time, and order a minimum of 1kg.

When it comes to cooking – time, ingredients, equipment and respect for the process are non-negotiable investments for her.

She has a network of trusted butchers for the different cuts of meats she needs. She travels all the way to Lucknow to buy iron sheets of distinct thickness for varied heat levels required for her slow cooked khad chicken (whole chicken, coated in a special marinade, wrapped in layers of paper thin flatbreads; slow-cooked in a pit), and tambe ke tabaakh (flat-bottomed copper basins) which she uses to prepare her inimitable mutton ke soolay (chunks of spiced meat, slow cooked in ghee, then hand rolled into kababs).

Even in keeping things basic, there’s an unrelenting stubbornness in Ahmed Ali’s daughter and the legendary Tunday Kababi’s niece. Her basic, is basically a series of laborious intricate processes that must aptly be worded as ‘anything but basic’. (Tunday Kababi was a one-armed chef from Lucknow whose descendants run the famous shop by the same name even today.)

The two most indispensable belongings of Zaibun Nissa’s culinary art are her traditional cooking equipment and Ahmed Ali ke nuskhe (her father’s recipes of special spice blends). She guards these two with her life. Her heirloom garam masala, she boasts, is a blend of 22 spices, prepared by her father.

When she laid out the spice jars and kewra (fragrant rose essence) for us to take a whiff, her eyes had an unmistakable glint of pride. The intoxicating scent of kewra filled the air, affirming the Mughlai essence of Zaibun Nissa’s craft.

These were creations of a genius who had left his legacy in steel jars full of aromatic combinations.

The advance ordering system at her kitchen ensures that there is no wastage of food and that enough time is spent cooking the food slowly to ensure quality. She avoids using the refrigerator as much as possible, and gets most of the meat delivered at the break of dawn, while there’s still a nip in the air. She doesn’t pack the food in takeaway containers and gives you a specific time to pick up the food so there’s no reheating involved.

Through the years, the world has seen the technique of food preparation progress from slow to fast to processed. Hands, pit fires and earth ovens replaced by food processors, electric ovens and microwaves. Now, when the world is slowly coming full circle, embracing the workmanship it grew tired of, Zaibun Nissa is right there, waiting for the automation chasers to come back and see what they were missing. She’s waiting with her angeethi, her tabaakh, and her hands, ready to welcome you with the good ol’ painstakingly cooked meal. She’s still here, refusing to change her methods, refusing to fall for innovation that relies solely on machines, unknowingly establishing herself as the quiet flag-bearer of the slow food movement – a term she has never heard of.

After a three-hour long afternoon chat with her, we decided that we’d come back two days later to pick up the food around 8 pm. At 7:55 pm she called me, “haan, late ho gaye, kab aaoge? Mere Namaaz ka time ho raha hai” (you are late, when will you reach? It’s almost time for my prayer.). It isn’t easy to pacify Zaibun Nissa over the phone. I apologised to a disconnected call. 10 minutes later we jumped out of the car, and ran inside.

“Aap zara jaldi aate, khaana thanda ho raha hai,” (You should have come a little early, the food is getting cold) she said affectionately. For Zaibun Nissa, everything is about the timing of food. If you don’t eat it hot, you haven’t done justice to her cooking. She smiled and tossed soft, crumbling, hot soolas into our hands. The soola kababs were delicate to touch and crumbling without effort, barely reaching the mouth in a piece and melting instantly. This gosht (tender meat), was the consequence of meticulous sourcing and philosophic cooking. Enveloped in ground spices and pure ghee, it is undoubtedly, the strongest memory of Zaibun Nissa’s sensational cooking.

The mutton was succulent. The deliberation with which it had been cut into small enough pieces, ensured that the marinade found its way into the substance of the kababs, and made it uninterruptedly smooth while retaining its meatiness.

A combination of finely ground dry nutmeg and green cardamom, another signature masala by Ahmed Ali specially crafted for dry preparations like shami kababs (meat and chickpea kebabs) and soolay, combined with a ginger garlic paste was worked into the meat as marinade.

The kababs were shallow fried in desi ghee (slow-cooked clarified butter) which left its hearty presence in the air and lasting impression on our souls.

Zaibun Nissa then lifted the lid off her special mutton nihari – an Indian mutton stew cooked very slowly along with its bone marrow – and instantly, every ounce of air was doused in the aroma of Ahmed Ali’s signature spice blend.

Prominent notes of cinnamon, red chilli, cloves, amchur (dry mango powder), chaat masala (a tangy mix of Indian spices), charcoal smoke, desi ghee and kewra first struck our senses individually, then blended together revealing its hedonistic, intense character.

Noticing our stupefied expressions, she explained that cooking well – in essence – is one’s mastery in administering heat and roasting masalas.

Zaibun Nissa explains detailed processes with an ease that makes her craft look utterly simple. That simplicity of course, has emerged from years of methodical cooking and the little fixes – like her handy spice blends and an efficient network of mise en place crew – she has pioneered, to become the master she is today.

She forgets a lot now, but her andaaza (guesstimate) – the only unit of measurement used in Indian cooking – is so good that her forgetfulness never interferes with taste. Although she did put salt twice in the khad chicken once, she admits.

“Maine apni nawasiyon ko sikha diya hai, unko karna hoga toh kar lengi. Razeena badi intelligent hai, dekh dekh ke sab seekh gayi hai”, (I’ve taught my granddaughters, it’s up to them now, they’ll pursue it if they wish to, Razeena is very intelligent, she has watched and learned everything). She mentions this casually but the hope in her eyes is unmistakable.

We returned to the hotel, ordered rotis and ate the food with a sense of disbelief. The nihari (slow-cooked mutton stew) was a superlative experience. Robust flavours but a delicately refined texture – it tasted of contentment. “This must be impossible to replicate,” someone muttered. Nobody spoke. The clinking of cutlery was only occasionally interrupted by exclamatory monologues and spice-induced sniffles.

Mughal influences on the palatial kitchens of Rajasthan have modified with time. Zaibun Nissa’s cooking might be the last of what is left of Ahmed Ali’s magic, that once captivated the nobility of Rambagh Palace. The heaviness of this realisation hit us just when we polished off every bit of food she had lovingly prepared for us. But we also found some reassurance in Razeena’s dedication to honour her nani (grandmother) and sustain Zaibun Nissa’s Kitchen.

I called her a few months ago, “Aapko Eid bohot bohot Mubarak ho,” (wish you a very happy Eid) I yelled over all the festivities surrounding her. “Shukriya, mai aapse baad mei baat karti hun, mehmaan aaye hue hain abhi, mai zara busy hun,” (Thank you, I’ll talk later, I have guests over, I’m busy) Zaibun Nissa yelled back and disengaged. Nothing had changed.

Translations and detailed descriptions are provided to give a better understanding of the story to people from different cultural backgrounds across the globe.

Masha Allah she have the god gifted talent she have magic in her hand Allah gave him long and healthy life so that we can enjoy delicious dishes from her

Absolutely, she is truly gifted! 🙂

Wonderful writing , such detailed coverage of everything! Thoroughly enjoyed the article.

Thank you so much for taking the time to read it. Glad you enjoyed the story! 🙂